EBITDA is a commonly used profit metric that represents a ‘proxy for Cash Flow.’ However, analysts must be careful when analyzing EBITDA because it excludes the impact of Depreciation & Amortization, Interest, Taxes, Capital Expenditures, and the impact of Changes in Net Working Capital. In this article, you will learn the definition, common uses, and pitfalls Analysts encounter with EBITDA.

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

- What is EBITDA?

- What are the Origins of EBITDA?

- How do you calculate EBITDA?

- What is 'Adjusted EBITDA?'

- Why does EBITDA matter?

- How is EBITDA used in real life?

- Common Application #1: Assessing Profitability

- Common Application #2: Comparing Companies

- Common Application #3: Assessing Debt Burden vs. Cash Flow

- Common Application #4: Creating Valuation Multiples

- Common Point of Confusion #1: EBITDA vs (Unlevered) Free Cash Flow

- Common Point of Confusion #2: EBITDA vs EBIT

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Related Links

What is EBITDA?

EBITDA stands for Earnings, Before Interest, Taxes, and Depreciation.

EBITDA is one of the most common Profit metrics in the Finance world.

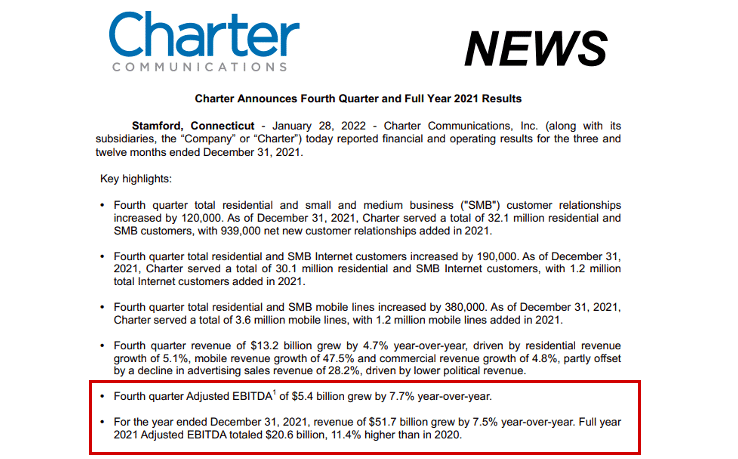

Company management teams often report EBITDA when they release Quarterly Earnings.

Below is a sample report from the Cable and Internet services provider Charter Communications (‘Spectrum’).

What are the Origins of EBITDA?

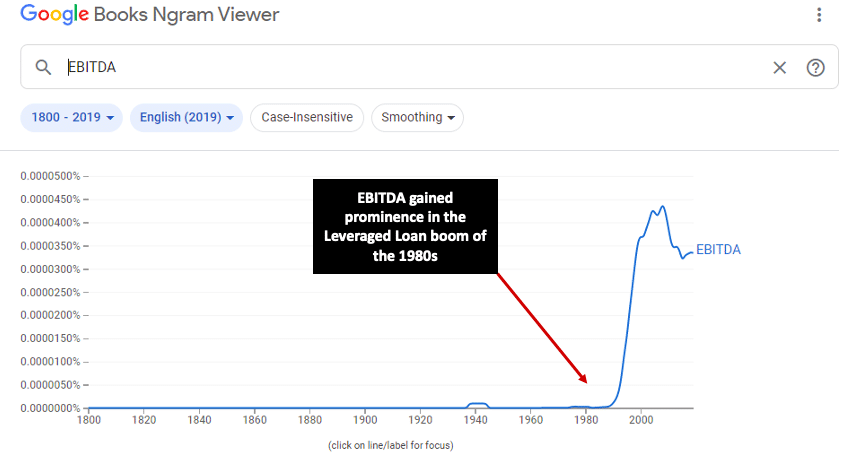

The term EBITDA grew in popularity during the Leveraged Loan boom in the 1980s but has remained popular through today.

Despite its shortcomings (which we will discuss), EBITDA’s can be calculated easily, which is likely the main driver of its popularity.

How do you calculate EBITDA?

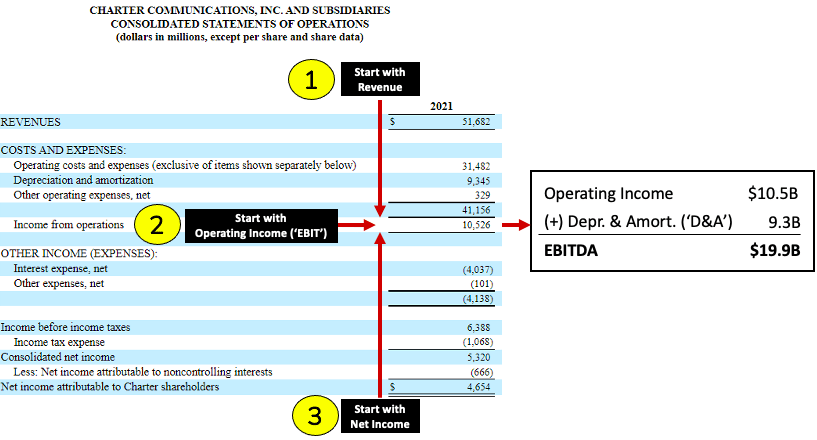

When looking at a typical Income Statement, you can work to EBITDA a few different ways, as you can see below:

3 Ways to Work to EBITDA

- Revenue → EBITDA:

Start with Revenue and work down to Operating Income. Then add back Depreciation and Amortization.

- Operating Income → EBITDA:

Start with Operating Income (‘EBIT’). Then add Depreciation & Amortization.

- Net Income → EBITDA:

Start with Net Income and work up reversing all items up to Operating Income. Then add back Depreciation and Amortization.

Companies often present EBITDA on a ‘Last Twelve Months (LTM)’ or ‘LTM EBITDA’ basis.

However, Companies (or Analysts) may also present EBITDA on a ‘Next Twelve Months (NTM)’ or ‘NTM EBITDA’ basis.

What is ‘Adjusted EBITDA?’

Note that EBITDA is considered a ‘Non-GAAP’ metric.

As such, Companies are not required to disclose EBITDA.

Further, because EBITDA is a ‘Non-GAAP’ metric, management teams have latitude in how they report EBITDA.

More specifically, Companies often report an ‘Adjusted EBITDA’ that excludes non-recurring (‘one-time’) Revenue and Expense items.

It is critical to understand the bridge to Adjusted EBITDA as a Financial Analyst.

Fortunately, most Public Companies provide a bridge when they report Adjusted EBITDA, as you can see in the excerpt below from Charter Communications (‘Spectrum’).

Why does EBITDA matter?

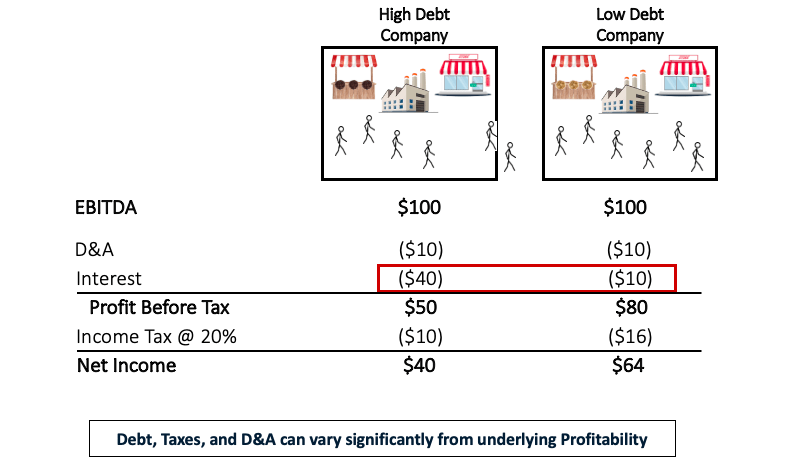

EBITDA allows us to compare the profitability of a Business to peer companies on an ‘apples-to-apples’ basis.

More specifically, EBITDA shows the Profit of a Company excluding the impact of:

- Interest on Debt.

- Income Taxes.

- Depreciation and Amortization (non-cash charges).

- Capital Expenditures + Net Working Capital (NWC)

The aim of the EBITDA calculation is to make a quick assessment of the Cash Flow generation potential of a Business.

In fact, EBITDA is often referred to as ‘Cash Flow Proxy’.

However, as we will discuss below, EBITDA is not true Cash Flow.

Now let’s take a look at how Analysts use EBITDA on the job.

How is EBITDA used in real life?

EBITDA is particularly prevalent in the following areas of the Buy-Side or Sell-Side:

- Investment Banking.

- Private Equity.

- Debt (‘Credit’).

- Corporate Finance / M&A.

There are a few common uses of EBITDA in real life:

- Assessing Profitability (‘EBITDA Margin’).

- Comparing Companies with Different Levels of Debt and Capital Intensity.

- Assessing a Company’s Debt (Interest) burden vs. Cash Flow.

- Creating Valuation Multiples.

Common Application #1: Assessing Profitability

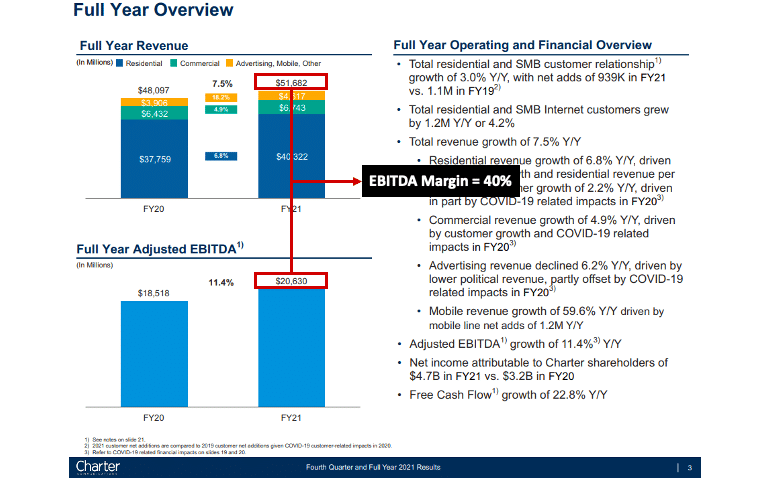

EBITDA helps us analyze a Business’ profitability relative to Revenue by calculating EBITDA margin.

To calculate EBITDA margin, we divide EBITDA dollars by Revenue dollars.

EBITDA margin is a percentage-based calculation. As a result, we can assess profitability per dollar of Revenue for Companies of any size.

Common Application #2: Comparing Companies

It’s not a coincidence that EBITDA is common in Investment Banking (IB) and Private Equity (PE).

In both IB and PE, a core activity is re-configuring a company’s mix of Debt and Equity (the ‘Capital Structure’).

EBITDA helps Investment Banking and Private Equity professionals analyze and compare companies without incorporating the impact of Debt.

Common Application #3: Assessing Debt Burden vs. Cash Flow

A core component of a Lender’s role is to assess whether a Company has sufficient Cash Flow to repay its Interest and Principal payment obligations.

As a result, Credit Analysts look at EBITDA as a rough proxy for Cash Flow.

As such, Analysts use EBITDA as a ‘shortcut Cash Flow’ metric in the most common Leverage Ratio (Net Debt / EBITDA) and Coverage Ratio (EBITDA / Interest).

In the report below by Charter Communications (‘Spectrum’), we can that the company reports the Debt / EBITDA ratio.

In addition, because EBITDA is not Cash Flow, we also see a bridge that helps Investors and Lender to see the differences between EBITDA and true Free Cash Flow.

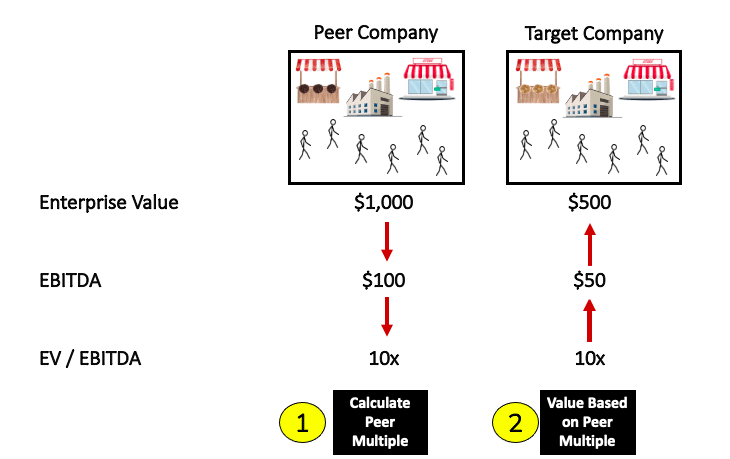

Common Application #4: Creating Valuation Multiples

A final common application of EBITDA is Valuation.

Analysts will often use peer Enterprise Value (EV) / EBITDA to assess the relative valuation potential of peer Companies.

As you can see above, an Analyst can calculate peer multiples, and then apply the peer multiple to the EBITDA of the Company they would like to value.

This calculation creates an estimated Valuation (again ‘Enterprise Value’) for the Target Company.

Common Point of Confusion #1: EBITDA vs (Unlevered) Free Cash Flow

Finance professionals often refer to EBITDA as a ‘Proxy for Cash Flow,’ but EBITDA is not actual Cash Flow!

As you can see below, EBITDA excludes many items that are part of the full Unlevered Free Cash Flow calculation.

Practically, however, it is much easier to quickly calculate EBITDA, hence the widespread usage of EBITDA in Finance.

With that said, in practice, Investment Bankers, Investors, and Lenders understand this shortcoming and make mental adjustments as they analyze companies.

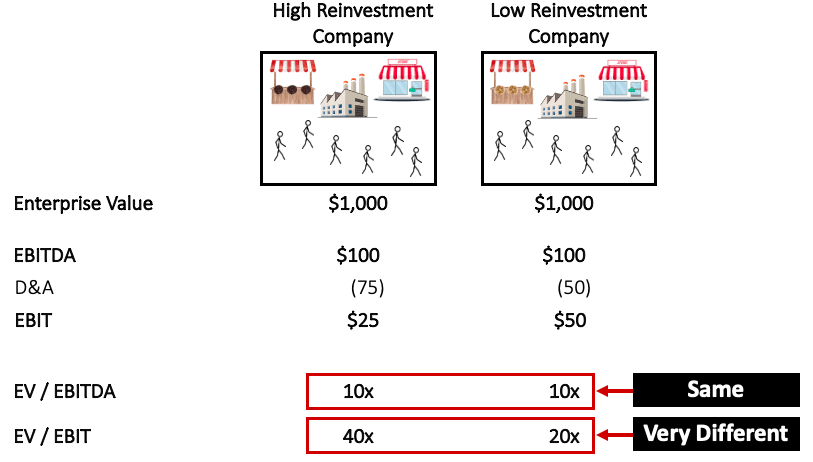

Common Point of Confusion #2: EBITDA vs EBIT

EBITDA is different from EBIT in that it excludes the impact of Depreciation and Amortization (‘D&A’).

The critical point to understand here is that excluding D&A can create significant distortions.

As you can see above, this is particularly true when two companies in the same industry have significantly different reinvestment requirements.

Two companies can appear the same on an EBITDA basis, but quite different on an EBIT basis.

Frequently Asked Questions

EBITDA stands for Earnings, Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. It is a widely used profitability metric in the Finance world.

EBITDA is a ‘proxy for Cash Flow’ that allows us to quickly assess the Cash Flow generation potential of a Business without having to make tremendously detailed calculations.

There are three common ways to calculate EBITDA:

1. Revenue → EBITDA: Begin with Revenue and work down to Operating Income. Add back Depreciation and Amortization.

2. Net Income to EBITDA: Begin with Net Income and work up, backing out all items up to Operating Income. Add back Depreciation and Amortization.

3. EBIT → EBITDA: Begin with Operating Income (‘EBIT’). Add Depreciation & Amortization

There is not a ‘good’ absolute dollar level of EBITDA. Rather, we typically analyze EBITDA relative to Revenue (called ‘EBITDA Margin.’) It is important to note that EBITDA margin must be viewed in the context of a Company’s industry (and a variety of other factors). For example, a ‘high’ EBITDA Margin for a Distribution business might be a ‘low’ EBITDA margin compared to that of a Cable Company.

EBITDA is different from Gross Profit. We calculate Gross Profit as Revenue – Cost of Sales (including Depreciation and Amortization). In contrast, we calculate EBITDA as Revenue – Cost of Sales (excluding Depreciation and Amortization)- SG&A Expense (excluding Depreciation and Amortization).