‘What is a Hedge Fund?’ is a question that usually ends with more confusion than clarity. In this guide – written by an industry insider who worked at a multi-billion dollar Hedge Fund – we make it simple.

In this article, you will learn:

- What is a Hedge Fund? (History, Typical Investments, and Strategies)

- How do Hedge Funds Work? (Legal Structure, Long vs Short, Fees, Gross vs Net Exposure)

- Why are Hedge Funds considered risky? (Leverage, Liquidity, Derivatives)

- How to Invest in a Hedge Fund? (Legal Requirements, Minimum Investment)

- What does a Hedge Fund Manager Do? (Day-To-Day Role, Compensation)

- Hedge Fund vs Private Equity and Mutual Funds

Estimated reading time: 34 minutes

- TL;DR

- Want To Learn More About Finance?

- What is a Hedge Fund?

- What is a Hedge Fund? – Inner Workings

- What is a Hedge Fund? – Risks

- What is a Hedge Fund? – How to Invest

- What is a Hedge Fund? – Hedge Fund Managers (+ Compensation)

- Hedge Funds vs. Private Equity vs. Mutual Funds

- Wrap-Up: What is a Hedge Fund?

- About the Author

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Related Links

TL;DR

- A Hedge Fund is ‘pooled investment vehicle‘ that invests primarily in publicly-traded securities to generate returns for investors.

- Hedge Funds are unique because they ‘Hedge’ their portfolios by ‘Going Short‘ in addition to ‘Going Long.’

- Investors in Hedge Funds fund face unique risks to due to the use of Leverage and Derivatives as well as limited Liquidity.

- While Hedge Fund Managers can earn substantial sums, managing a fund and reaching the top of the stack is incredibly difficult.

Want To Learn More About Finance?

Check out all of our (free) deep-dive articles in our Analyst Starter Kit:

What is a Hedge Fund?

Hedge Funds can be incredibly confusing to understand.

This article will provide plain-English, illustrated explanations to help you understand everything you would want to know about Hedge Funds.

Let’s start with how do we define ‘Hedge Fund?’

At a very high level, Hedge Funds are investment vehicles that pool money to invest on behalf of their investors.

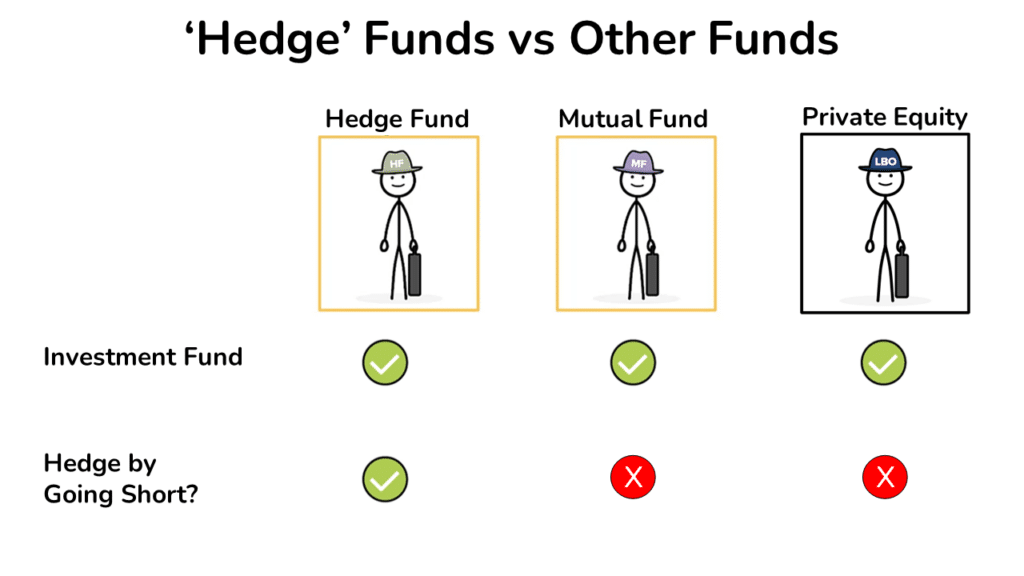

The big difference between Hedge Funds and nearly every other type of investment fund is that Hedge Funds aim to ‘Hedge Out’ certain risks within their investment portfolio.

Let’s jump ahead here and look at how Hedge Funds execute this strategy.

How Does ‘Hedging’ Work?

Let’s begin by explaining how Hedge Funds can ‘Hedge’ using an example that will be familiar if you have ever invested in a Stock.

Check out our Stocks vs Bonds animated explainer video for a brief overview of how Stocks work.

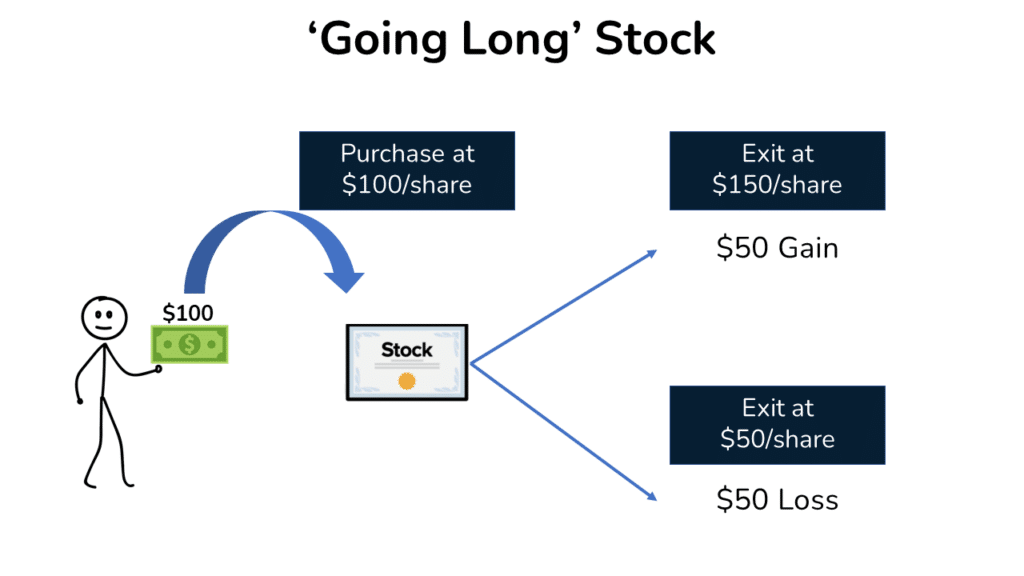

When a typical investor buys a stock, they make money when the Stock increases in value and lose money when the Stock decreases in value.

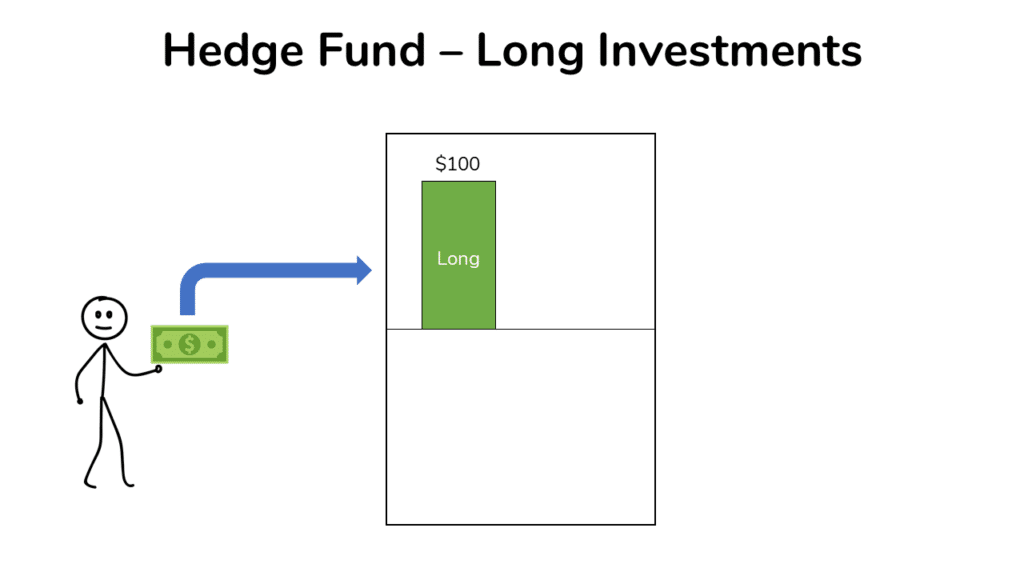

We call this process ‘Going Long.‘

In this quick video on ‘Going Long,’ we walk through a simple, animated explanation of how this process works.

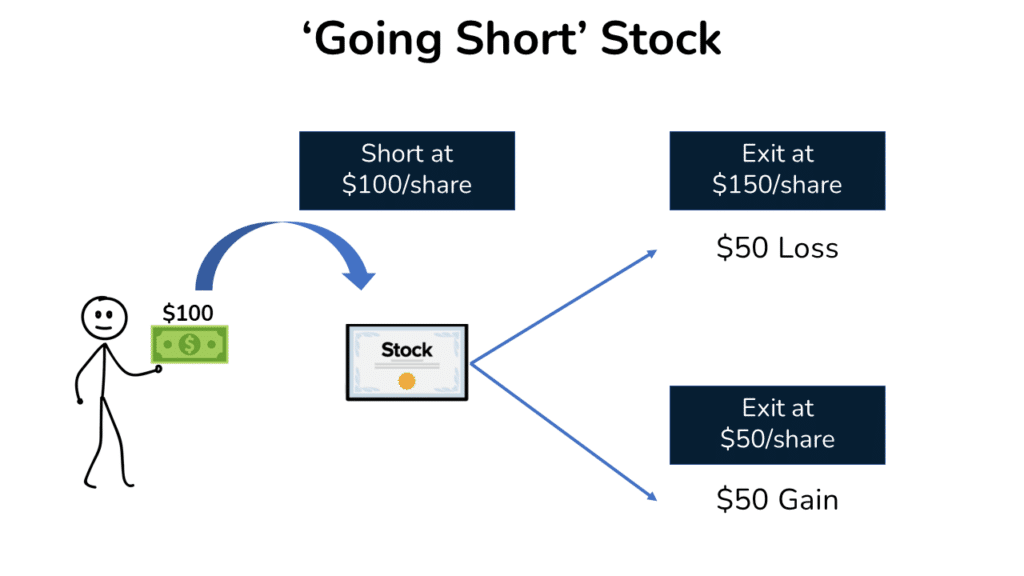

Conversely, an investor can also ‘sell short‘ a Stock.

When an Investor goes Short, they make money if the Stock decreases in value and will lose money if the Stock increases in value.

We call this process ‘Going Short.’

In this quick video on ‘Going Short,’ we walk through a simple, animated explanation of how this process works.

Now that we’ve covered the mechanics of Long vs Short, let’s look at how this applies to professionally managed Investment Funds.

To do that, we’ll compare Mutual Funds and Hedge Funds.

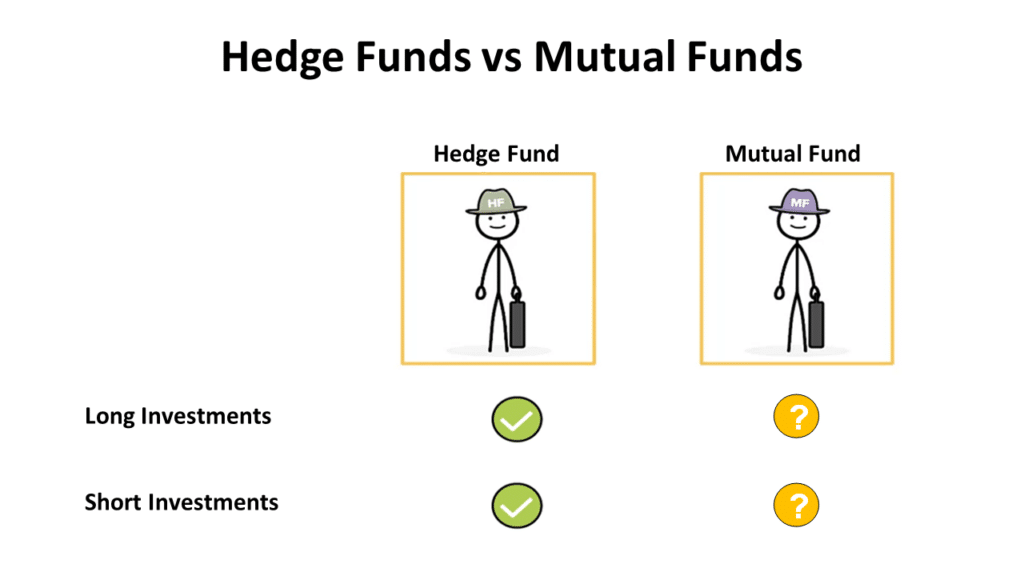

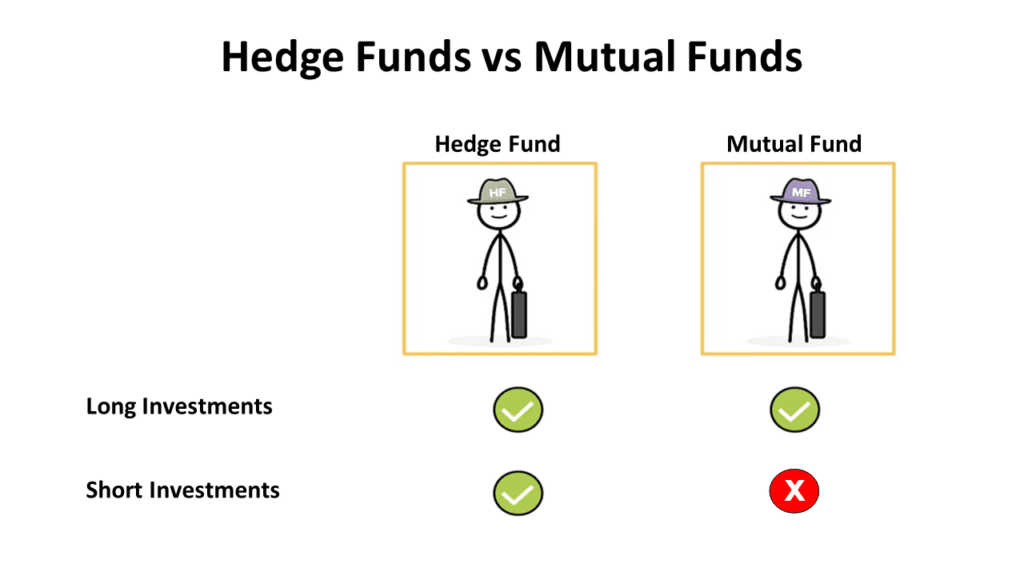

Mutual Funds (Long-Only) vs Hedge Funds (Long/Short)

Let’s start here by quickly defining what a ‘Mutual Funds’ does.

In short, Mutual Funds aggregate money from investors.

These funds typically have a defined strategy where they invest in either Stocks or Bonds.

Mutual Funds are often referred to as ‘Long-Only’ investors because they typically only ‘Go Long.’

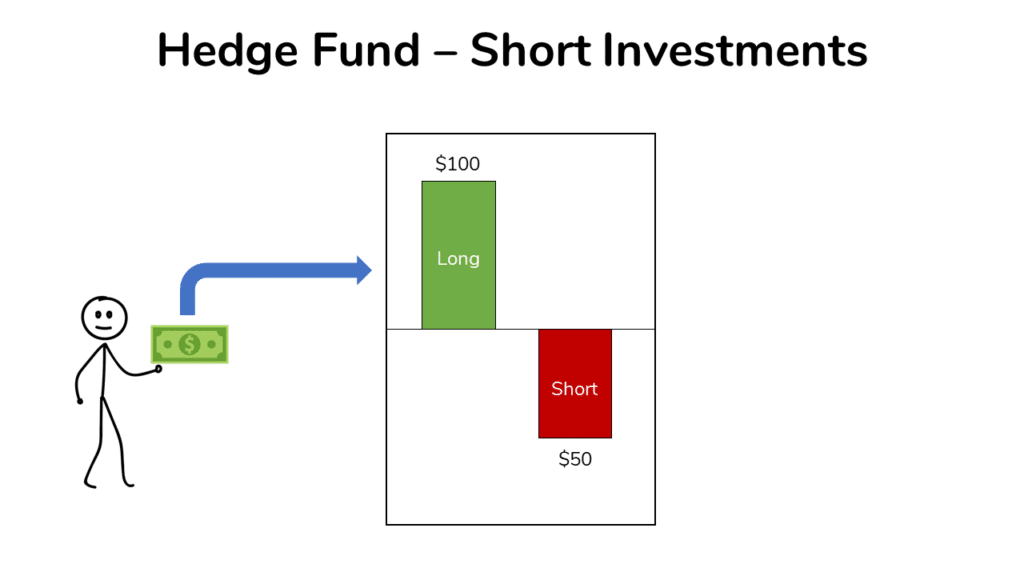

In contrast, Hedge Funds are called ‘Hedge’ Funds because they ‘Hedge Out’ the risk of their portfolio by simultaneously ‘Going Long’ and ‘Going Short’ different securities.

As we will see later in this article, the aim is to cancel out some of the market risks of a traditional ‘Long-Only’ portfolio.

If you are wondering, ‘where did this all come from in the first place?’, hop ahead to find out.

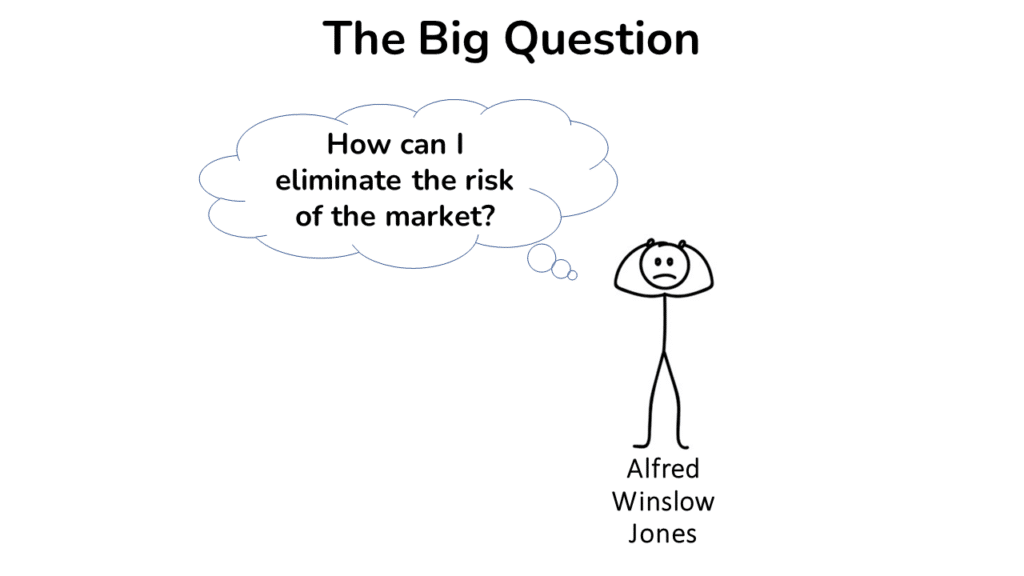

Where did Hedge Funds Come From?

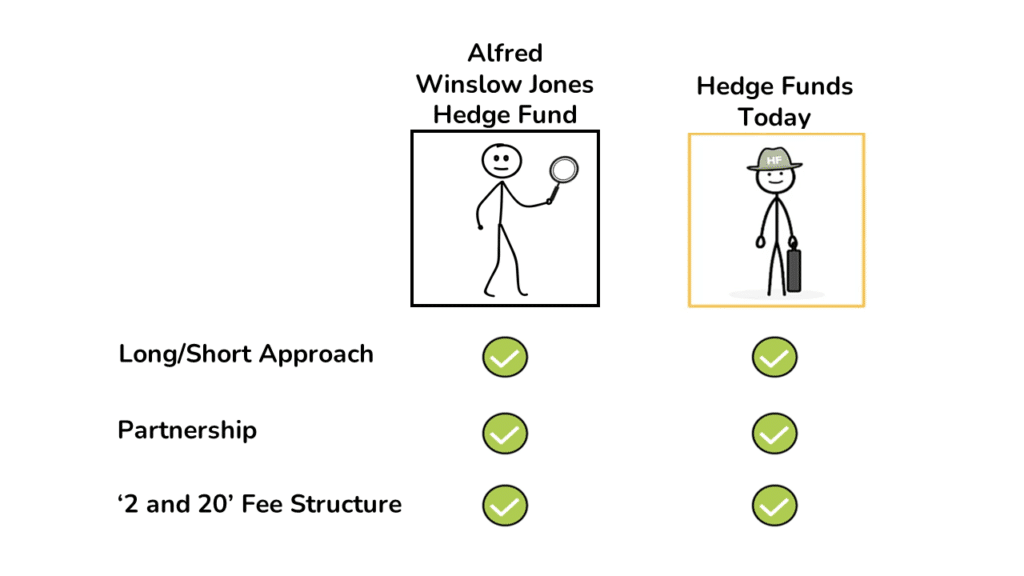

Alfred Winslow Jones is believed to have created the first Hedge Fund in 1949.

The idea for the Fund originated from Jones’ desire to lower overall market risk when investing.

To do this, Jones created a new type of Fund that would eliminate market risk by simultaneously going Long and Short different securities at the same time.

In taking this approach, Jones would be rewarded for simply betting correctly on investments, regardless of the market’s direction.

This approach gave rise to the term ‘Long/Short,’ which is essentially synonymous with ‘Hedge Fund.’

In this Quick Video, we walk through a brief, animated explanation of how a Hedge Fund manages its portfolios to go Long and Short at the same time.

Beyond inventing the Long/Short approach, Jones also organized his Fund as a Partnership, used Leverage (i.e., borrowing) to invest more than the money invested in the Fund, and invented a new fee structure.

To this day, nearly every Hedge Fund employs the same legal structure, uses Leverage, and employs Jones’ original fee structure.

In subsequent decades, many now-prominent investment firms like Soros Funds, Bridgewater, and Tiger Management have launched funds that mirror Jones’s structure and approach.

While there have certainly been ups and downs, Investors have found this investing approach attractive.

As a result, Assets Under Management (‘AUM’) for Hedge Funds have grown dramatically in recent decades.

According to Statista, Hedge Funds manage nearly $4 trillion of Assets as of the end of 2020.

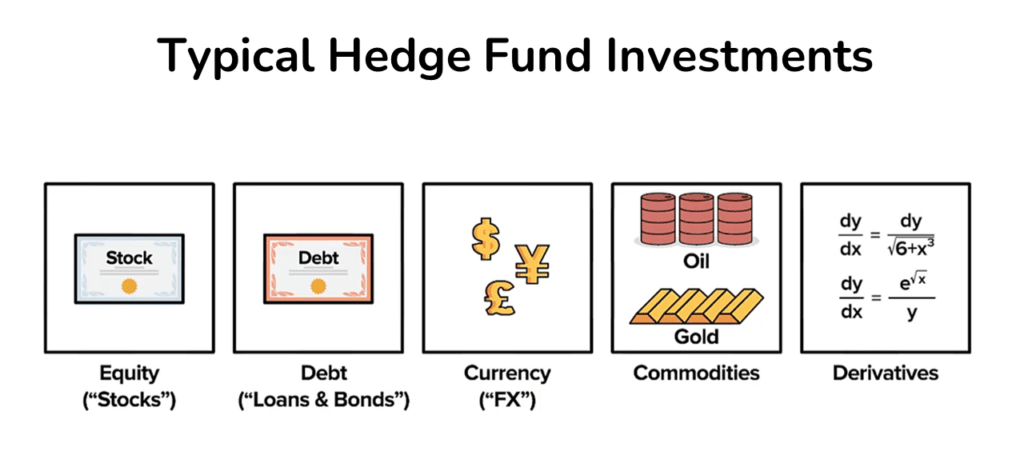

What do Hedge Funds Invest in?

Most Hedge Funds focus on a particular Asset Class (e.g., Stocks, Bonds, etc.) and/or Strategy, which the Fund Managers agree upon with their investors.

With that said, if the investors agree, a Hedge Fund can invest in basically anything.

Below is a summary of some of the most common types of Investments:

- Stocks (i.e., Equity) – units of Ownership of a Company (e.g., Google, Facebook, etc.).

- Bonds and Loans (i.e., Debt) – a variety of instruments ranging from Debt issued by Companies (‘Corporate’) to Debt issues by Governments (i.e., ‘Sovereign’).

- Commodities – any undifferentiated raw material ranging from Oil and Gas to Copper and Iron Ore.

- Currencies (‘FX’) – money issued by various governments around the world.

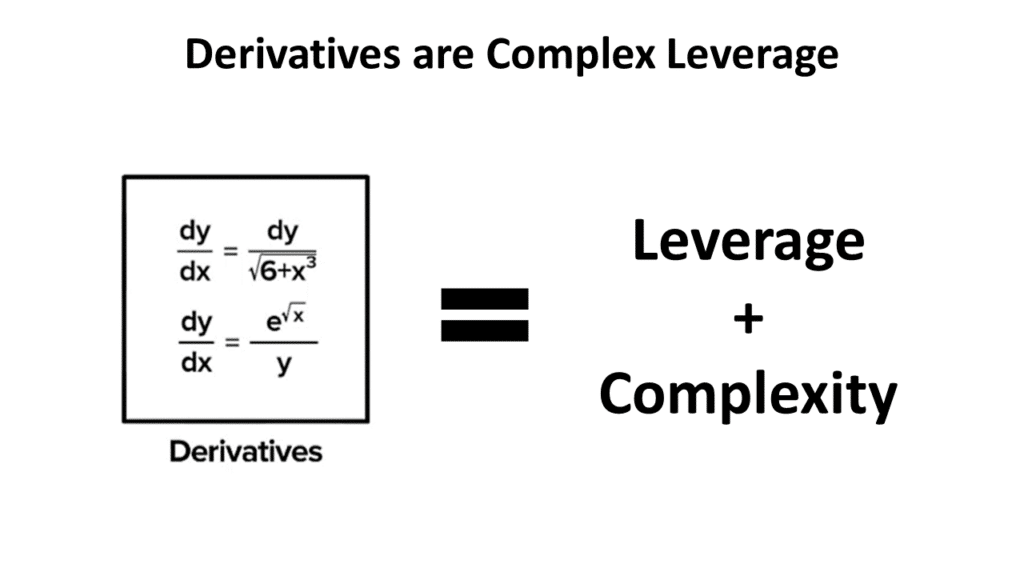

- Derivatives – complex securities like Options, swaps and futures that ‘derive’ their value from any other security.

A single fund can invest in all the instruments above, but as mentioned above, they often focus on just one or two.

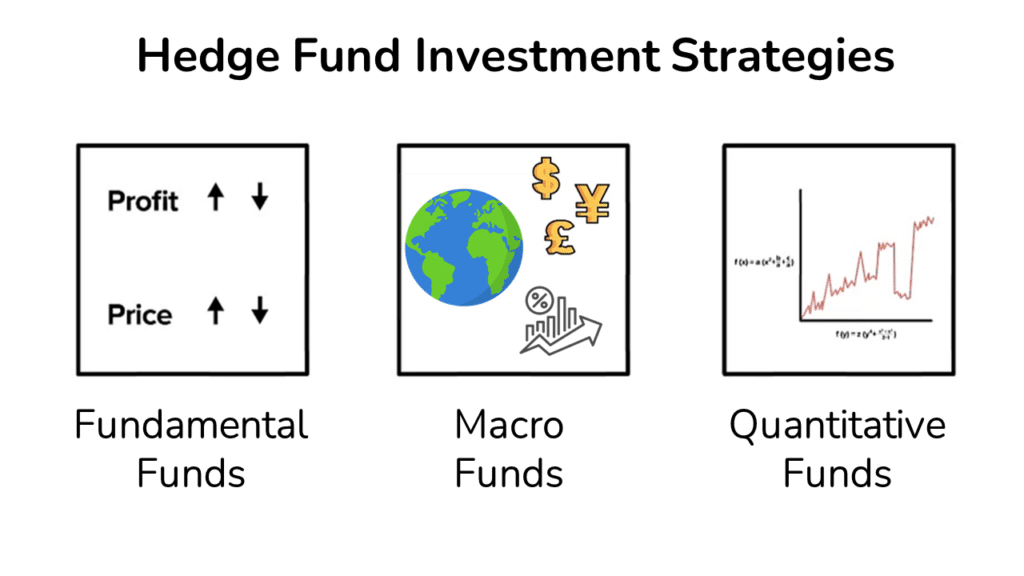

Typical Hedge Fund Investment Strategies

It is difficult to describe a ‘typical’ Hedge Fund because there are so many different strategies. But we will give it a try here!

Broadly speaking, Hedge Fund investment strategies fall into a few big groups: Fundamental Investing, Macro Investing, and Quantitative Investing.

Let’s dive into each Hedge Fund strategy and see how they operate.

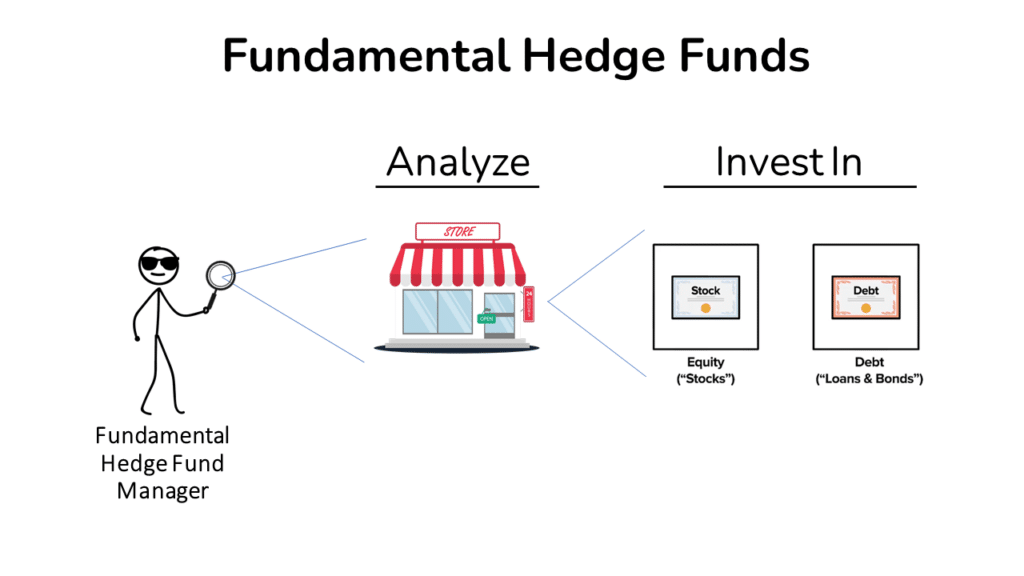

Fundamental Hedge Funds

Fundamental Hedge Funds invest in securities based on the underlying performance of the Business behind the security they purchase (Bond, Stock, Options, etc.).

There are a WIDE variety of strategies employed by Fundamental Hedge Funds:

- Traditional Long/Short Equity – go long and short individual Stocks based on future performance of the underlying Business.

- Event-Driven – make hedged investments in Stock based on upcoming business events (e.g., M&A, Restructuring, etc.) that will drive a change in the Stock price.

- Activist – take sizable stakes in companies and agitate for changes (e.g., operational improvement, acquisitions, and divestitures, etc.).

- Merger/Convertible Bond Arbitrage – make hedged investments in Stocks and Bonds to capture pricing discrepancies between related securities (e.g., convertible bond vs underlying common Stock) or the current price versus the acquisition offer price in an M&A scenario.

- Distressed Debt – invest in the Bonds and Loans of companies experiencing financing distress.

The list above is by no means exhaustive, but it captures some of the most common types of Fundamental Hedge Funds you will encounter.

The reason it is so hard to characterize a ‘typical’ fund is that many funds employ more than one of the strategies above.

With that said, a few of the most well-known Fundamental Hedge Funds are Tiger Global Management, Coatue Management, Third Point, and Pershing Square.

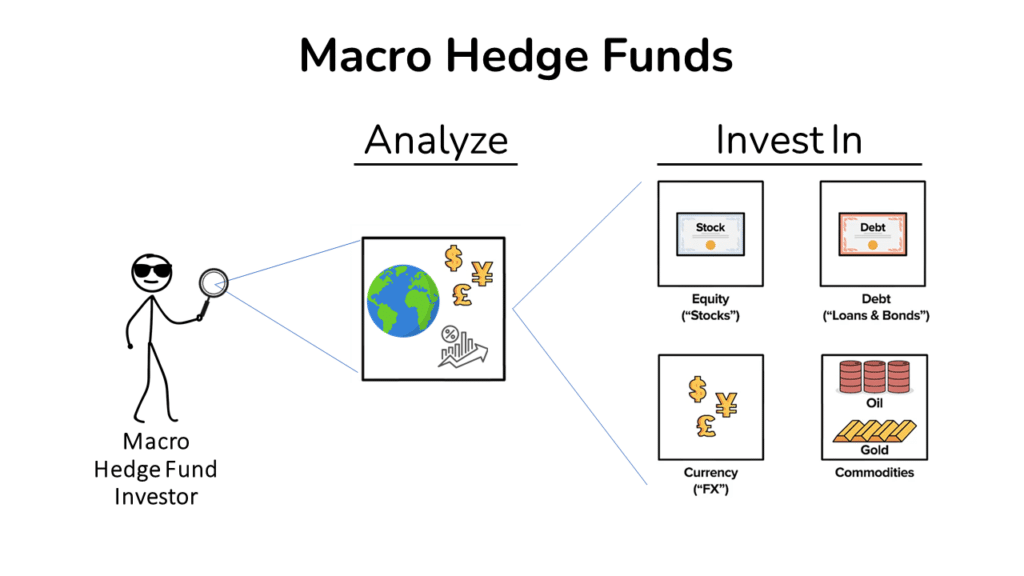

Macro Hedge Funds

Macro Funds focus on the bigger picture and invest based on anticipated trends in the global economy.

Instead of looking at individual securities, they invest based on significant economic shifts. in interest rates, geopolitical events, commodities, and currencies.

Macro Hedge Funds then invest in Stocks, Bonds, Currencies, etc. to capitalize based on shifts they expect to occur.

A few of the most well-known Macro Hedge Funds are Bridgewater Associates, Soros Funds, Tudor.

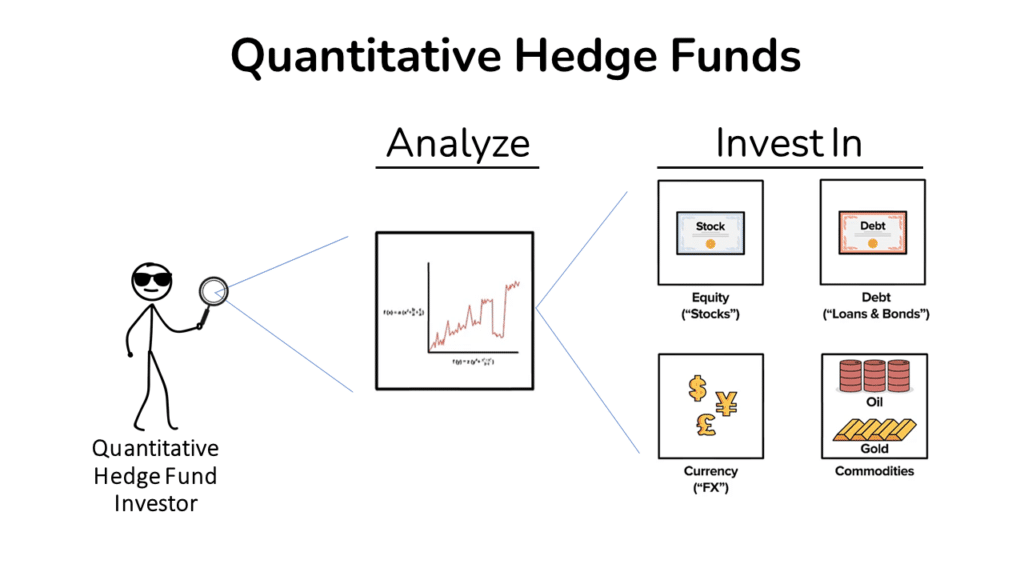

Quantitative Hedge Funds

Quantitative Funds (or ‘Quants’) invest based on complex algorithms, typically created by Math PhD’s.

These Funds apply the algorithms they create to nearly any type of liquid investment (Stocks, Bonds, etc.).

These funds are truly the ‘black box’ within the Hedge Fund world. And rightfully so.

Their proprietary algorithms create advantages that would quickly erode if other funds caught on.

This algorithmic approach of Quantitative Hedge Funds has created some genuinely astounding returns.

As an example, Renaissance Technologies (often called ‘Rentec’) has generated 39% annual returns after fees since 1988. These returns have generated dollar gains of over $100 billion.

A few of the additional well-known Quantitative Funds are D.E. Shaw, AQR and Two Sigma.

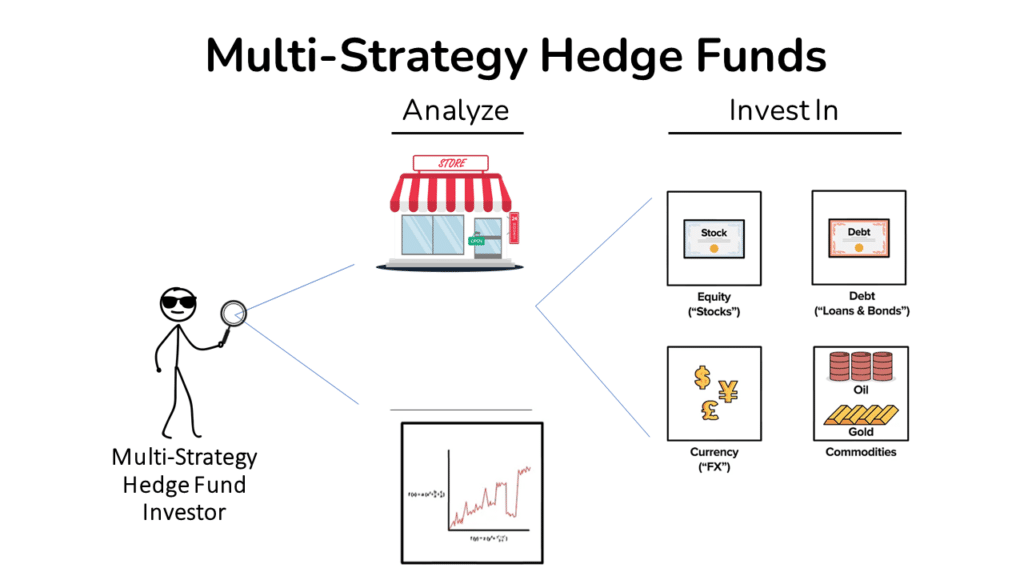

Multi-Strategy Hedge Funds

Next, just to keep things interesting, some funds run multiple strategies.

Those funds are simply called ‘Multi-Strategy’ funds or ‘Multi-Strat’ funds.

A few of the most well-known Multi-Strategy funds are Millennium Capital Partners and Citadel.

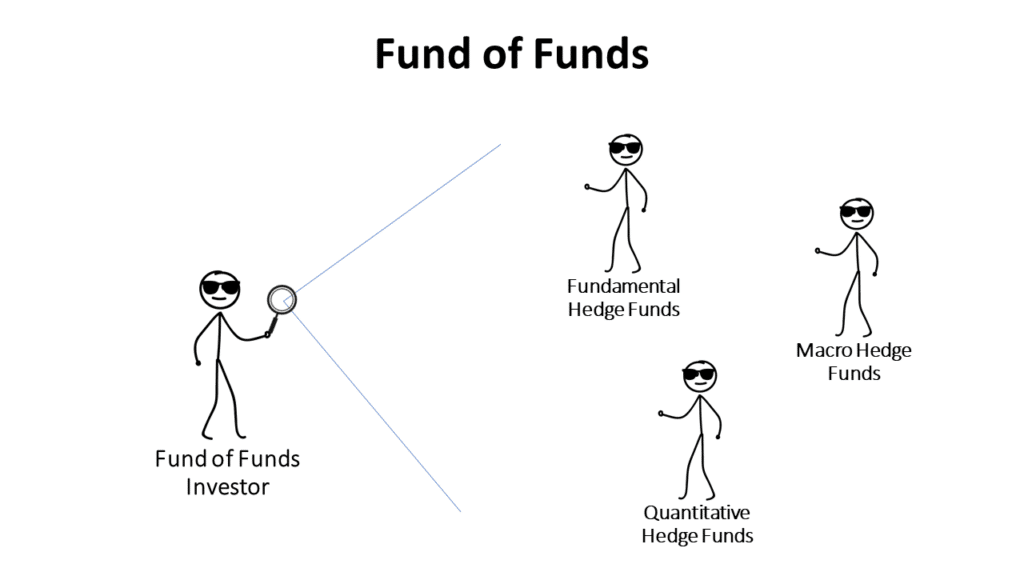

Fund of Hedge Funds (‘Fund of Funds’)

Last, we have Funds of Funds, which invest in other Hedge Funds.

Instead of investing in securities, these funds look for top-performing Hedge Fund managers to invest behind.

A few of the most well-known Fund of Funds are and Blackstone Alternative Asset Management and Grosvenor.

What is a Hedge Fund? – Inner Workings

Key Question(s) Covered:

- How do Hedge Funds work?

- What fees do Hedge Funds typically charge?

Now let’s take a peek behind the curtain and see how Hedge Funds actually work.

This next section will walk through legal structures, fees, and the complexities of managing a long/short portfolio.

In addition to creating the Long/Short approach of Hedge Funds, Alfred Winslow Jones also pioneered the usage of the partnership legal structure and the fee structure that is still widely employed with Hedge Funds today.

Typical Legal Structure of a Hedge Fund

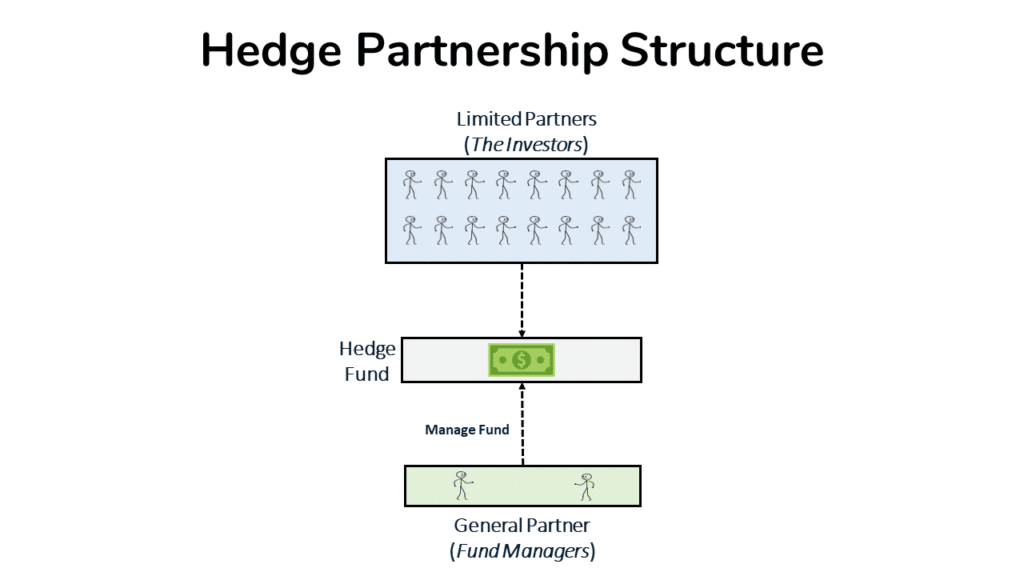

A few years after launching his Fund, Alfred Winslow Jones converted his Fund’s legal structure into a Partnership.

To this day, most Hedge Funds managers utilize the Partnership structure to launch their funds.

With this structure, the Hedge Fund founders (‘Partners’) own the General Partner (or ‘GP’), which manages the Fund’s day-to-day operations.

The Fund’s Investors are Limited Partners (or ‘LPs’) who contribute money to the Fund. But the LPs do not have any influence with regard to individual fund investments.

What fees do Hedge Funds charge?

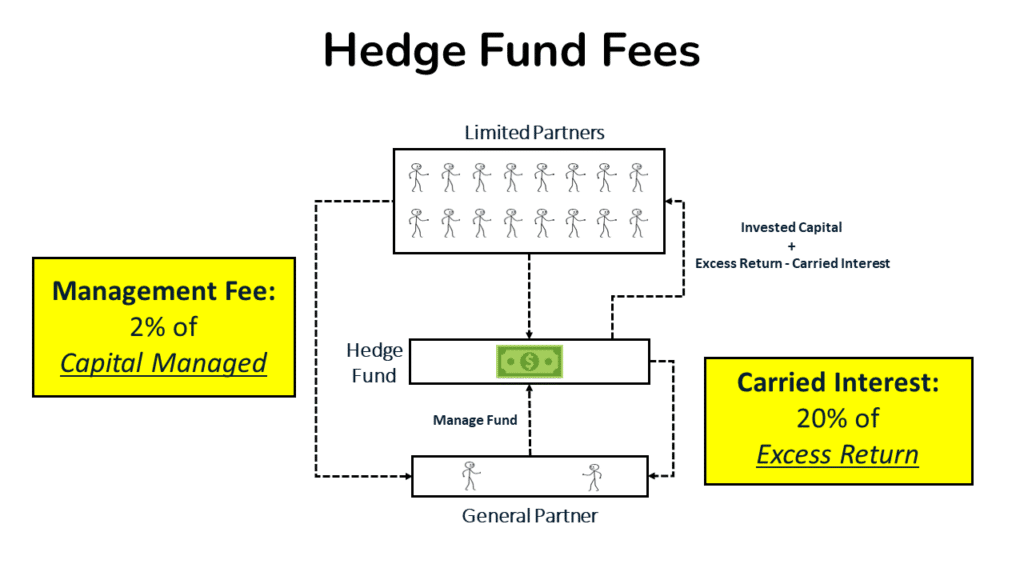

The fee structure that Hedge Funds employ also goes back to the original Fund started by Alfred Winslow Jones.

Jones employed a fee structure in which investors would pay 2% of Assets Managed and 20% of any Profit generated.

He likened this to the Phoenician ship captains who kept one-fifth of any profits generated on successful voyages. (Source)

This fee structure, often referred to as ‘2 and 20,’ remains the benchmark even today.

The 2% fee on Assets managed is referred to as a ‘Management Fee.’

And the 20% cut of profit generated is referred to as ‘Carried Interest’ or ‘Carry.’

It is worth noting that funds have experienced meaningful ‘fee compression’ in this structure in recent years.

A recent study by HFR, showed that most Hedge Fund managers charge Management Fees of 1.4% and Carried Interest fees of 16.4% on Average (more here).

Today, only the most sought-after funds are able to charge the full 2% Management Fee and 20% Carried Interest fee structure.

Constructing a Hedge Fund Portfolio

We said earlier in the article that Hedge Funds go Long and Short different securities.

In theory, a portfolio of Long investments offset by a portfolio of Short investments should hedge out the market.

In reality, managing a Hedge Fund portfolio is much more complicated.

Portfolio Risk Factors

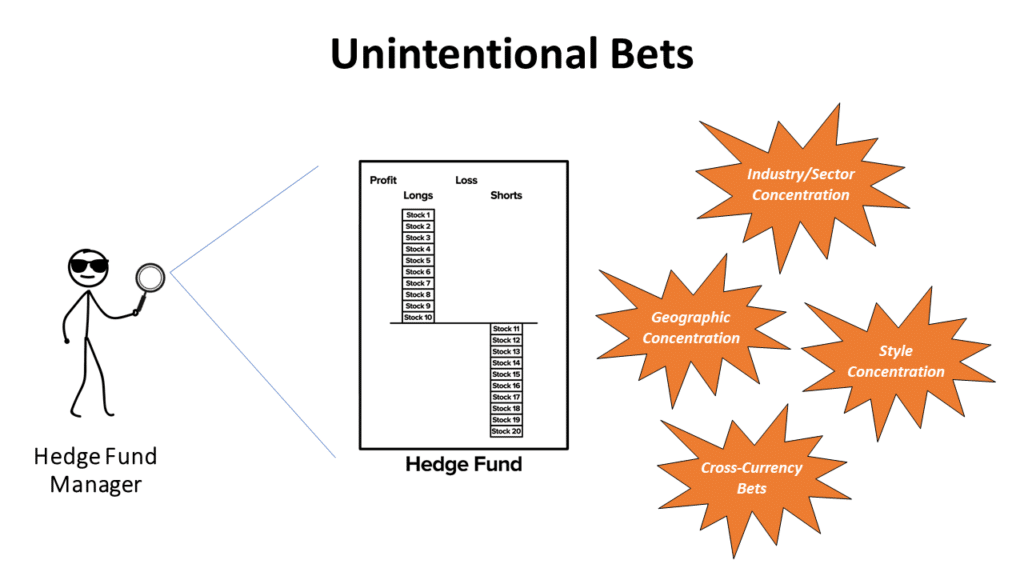

To begin with, a Hedge Fund Manager needs to monitor the portfolio for a variety of risk factors constantly.

Some common risk factors are:

- Industry/Sector Concentration

- Geographic Concentration

- Style Concentration (Growth vs. Value)

- Cross-Currency Bets

Every single day the market changes, and the portfolio shifts along with those changes.

Fund Managers need to actively monitor the portfolio for the above factors (and many others) to ensure they aren’t unintentionally exposing their funds to significant risks.

Longs vs. Short Exposure in a Hedge Fund Portfolio

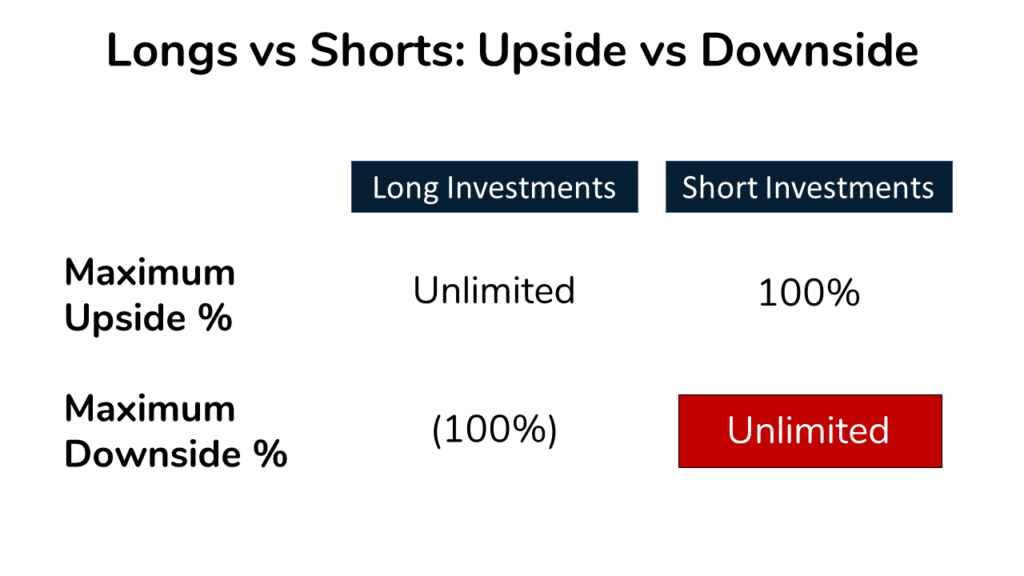

Next, there is the complexity of managing a Hedge Fund’s Short investments.

Briefly, Short Investments are much more challenging to manage due to:

- Unlimited Downside potential.

- More day-to-day volatility.

- The need for higher Number of Shorts vs Longs in a portfolio.

- Short Squeeze risk.

As a quick recap, remember that you lose money when you are Go Short an investment and it increases in value.

Because there is no limit to how high a Stock’s price can increase, an investor has unlimited downside with Shorts.

In addition, Short investments tend to be MUCH more volatile.

As a result, each Short investment tends to be much smaller than long investments as a percentage of the portfolio.

So, a typical fund might have 20 Long Investments but 40-60 Short investments to ensure they are not taking excessive risks on any individual short.

Short Squeezes and Meme Stocks

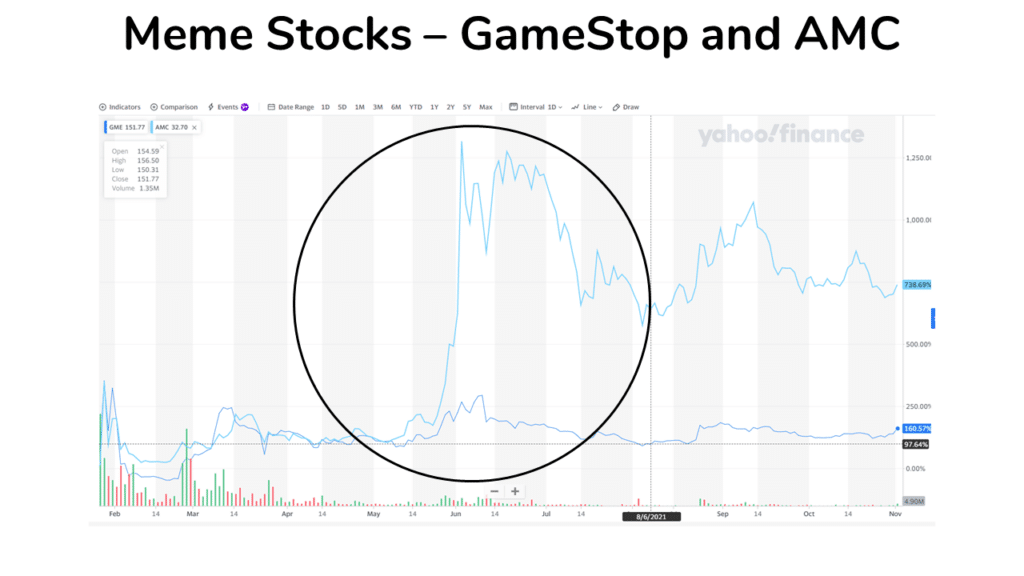

Beyond higher day-to-day volatility, there is the dreaded ‘Short Squeeze.’

Very briefly, a ‘Short Squeeze’ occurs when a Stock is heavily shorted, and all of the Investors head for the exits (i.e., the ‘Buy to Cover‘ to close out their position) at once.

This flurry of buying creates a circular boost to the Stock Price, resulting in dramatic price movements.

Over the last year, we have witnessed major short squeezes with ‘Meme Stocks’ like GameStop and AMC.

More on that here.

In summary, Shorting is a very challenging endeavor.

The challenges around managing shorts are a big reason why investors pay Hedge Fund Managers higher fees than managers of traditional investment vehicles like Mutual Funds.

Now we will look at the risks of Investing in a Hedge Fund.

What is a Hedge Fund? – Risks

Key Question(s) Covered:

- Why are Hedge Funds Considered Risky?

- What role do Leverage and Liquidity play in a Hedge Fund?

- What is Gross Exposure vs. Net Exposure?

In this section, we will dig into the risks involved with investing in Hedge Funds.

While we could probably come up with a longer list, there are a few key risk factors that you need to consider when investing in Hedge Funds:

- Liquidity

- Leverage

- Derivatives

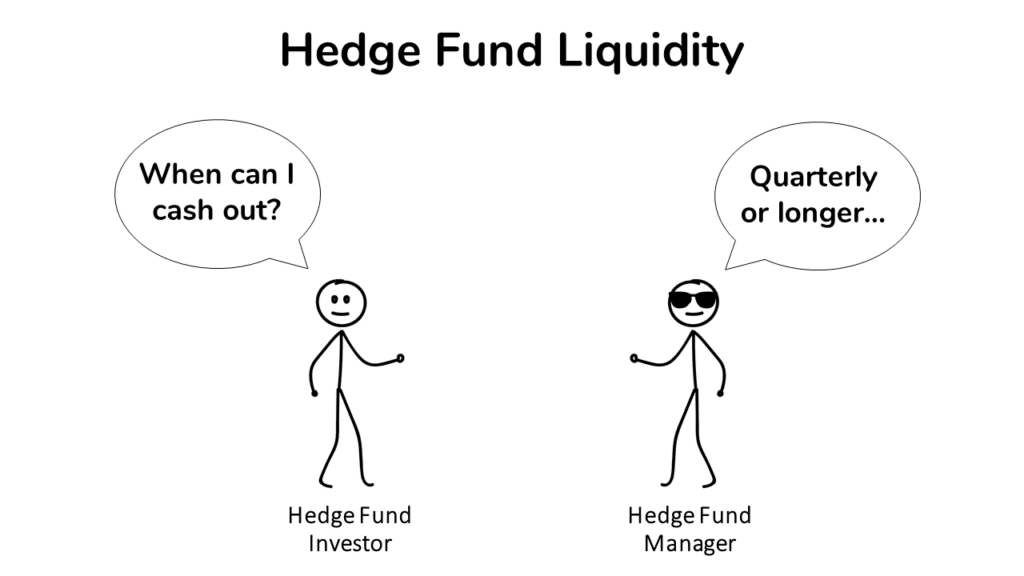

Hedge Fund Risk Factor #1: Liquidity

The first significant risk factor to consider is liquidity, or the ability to sell (i.e., liquidate) your investment in a Fund.

As a point of contrast, when you invest in a Mutual Fund, you can sell out of your investment every day.

With Hedge Funds, that is not the case.

Most Hedge Funds operate on a Quarterly redemption cycle in which you are only able to exit the Fund at the end of each quarter.

And as funds gain clout with investors, they often ‘Lock Up’ capital for much longer.

Lock-ups for highly sought-after funds can range from 6-12 months, with some extending for multiple years.

On the positive side, if you believe in the Hedge Fund manager, a fund lock-up works well because the Hedge Fund Manager can truly make long-term bets.

On the other hand, if the Fund begins to go in the wrong direction, you can do very little to exit until the lock-up ends.

Further Liquidity Constraints with Private Investments

In recent years, Hedge Funds have become heavily invested in Private Company investments which bear more resemblance to a traditional Private Equity approach.

For many funds, these investments have materially improved returns as noted in this recent article in the Wall Street Journal.

While these investments have increased returns, they have further decreased the level of Liquidity available to the investors in these Hedge Funds.

Hedge Fund Risk Factor #2: Leverage

The next significant risk factor to consider with Hedge Funds is Leverage.

To begin with, Leverage is just a fancy word to describe the level of Debt taken on by the Fund to make investments beyond the money provided by Investors.

Most Hedge Funds use some amount of Leverage in their Fund.

In short, if investors contribute $100 of money to the Fund, the Fund Manager will borrow to invest in securities with a value greater than $100.

Borrowing in this way increases the risk to the portfolio, as we will see below.

How Leverage Impacts Returns

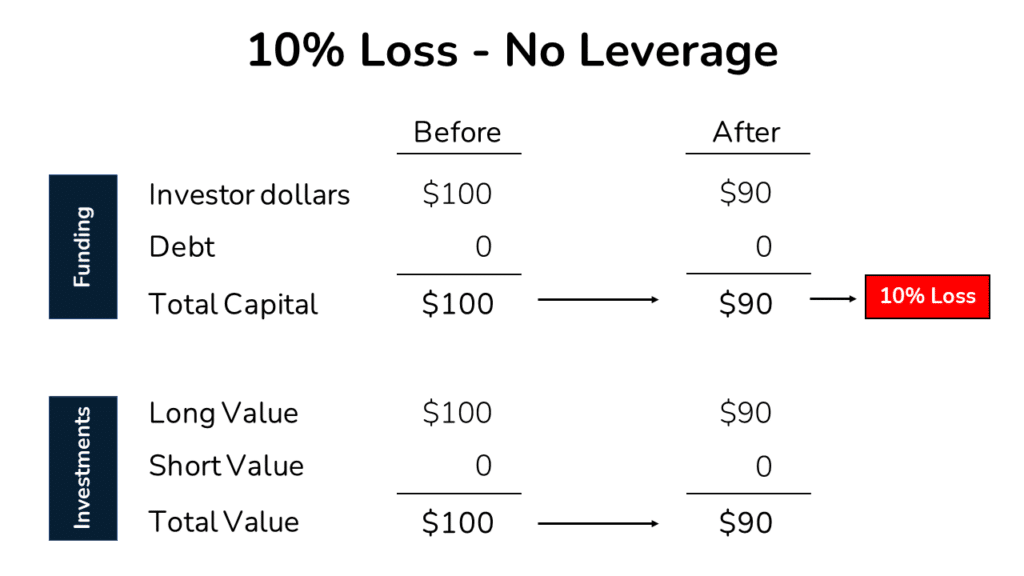

Let’s use a simple example to explain the impact of Leverage.

We’ll imagine that a Hedge Fund Manager takes in $100 in capital from Investors.

Let’s imagine that the Fund Manager only buys $100 of Stocks. And let’s imagine the portfolio declines in value by 10%.

In that case, the investors would lose 10% of their money.

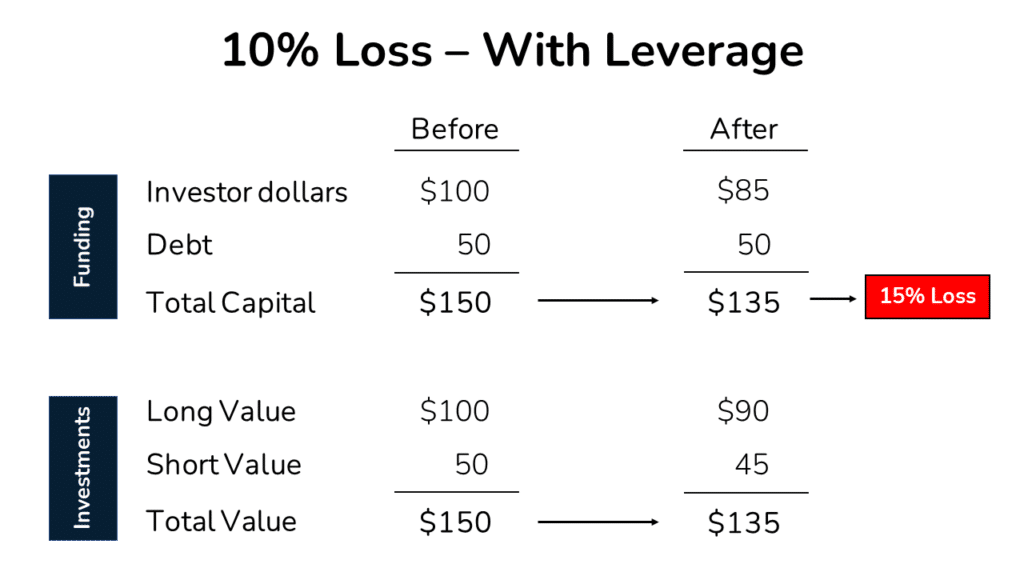

Now let’s imagine the Hedge Fund manager borrows to buy an extra $50 in Stocks.

In this case, a 10% decline in the total portfolio would result in a $15 decrease in value (or a 15% loss).

As you can see from this example, borrowing in this way increases the potential downside.

On the flip side, though, this also creates the opportunity for increased reward.

At this point, we need to discuss the terms ‘Gross Exposure’ and ‘Net Exposure.’

These terms will help us to see better how Hedge Funds use Leverage and how they Go Short to offset the risk created by the Leverage.

Hedge Fund Gross Exposure

With a typical Long/Short Equity Hedge Fund, the Hedge Fund manager will invest money by buying (‘Going Long’) $100 of Stocks.

At the same time, the Hedge Fund Manager would typically borrow beyond the $100 contributed by Investors.

But instead of Going Long, they Go Short, which offsets the overall risk of the portfolio.

Let’s say the fund manager ‘Goes Short’ an additional $50 of Stocks.

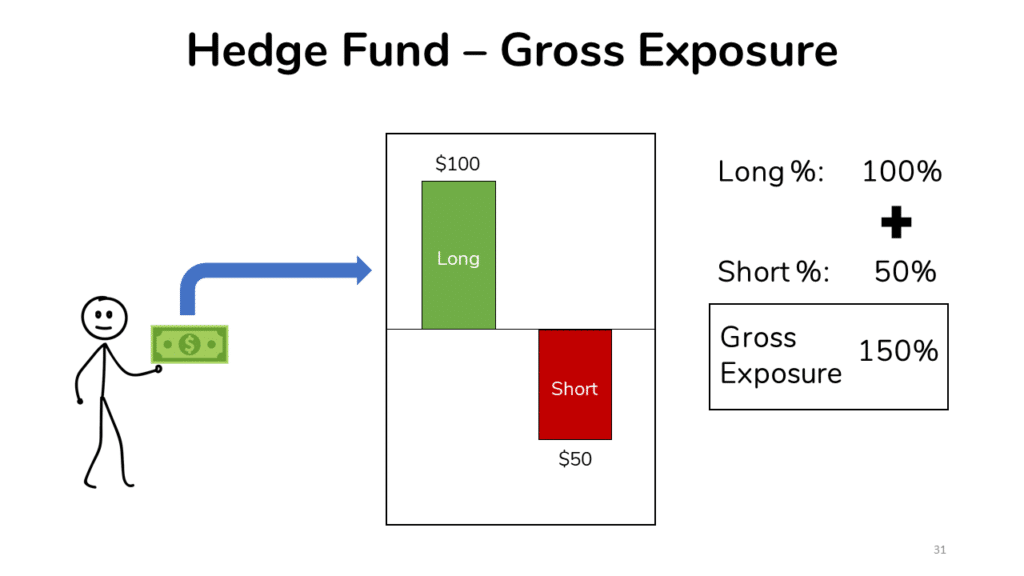

At this point, the Hedge Fund has $150 invested ($100 Long + $50 Short).

In short, the Hedge Fund is borrowing (i.e., using ‘Leverage’) to fund the additional $50 of Short investments.

In the Hedge Fund world, we would say that this Fund has 150% ‘Gross Exposure’ ($150 Total Investments / $100 Investor Capital) or that the Fund is running at a ‘150 Gross.’

Hedge Fund Net Exposure

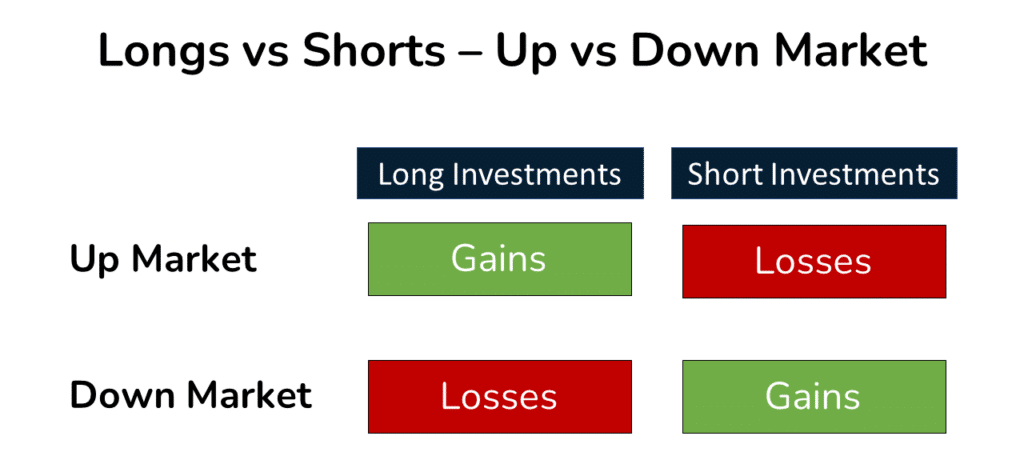

The catch here is that Long and Short Investments do not tend to move in the same direction.

When the market is going up, Longs will increase generate gains and the Shorts will generate losses.

As such, even though our Hedge Fund manager is borrowing in the scenario above, the shorts will likely offset the longs on any given day.

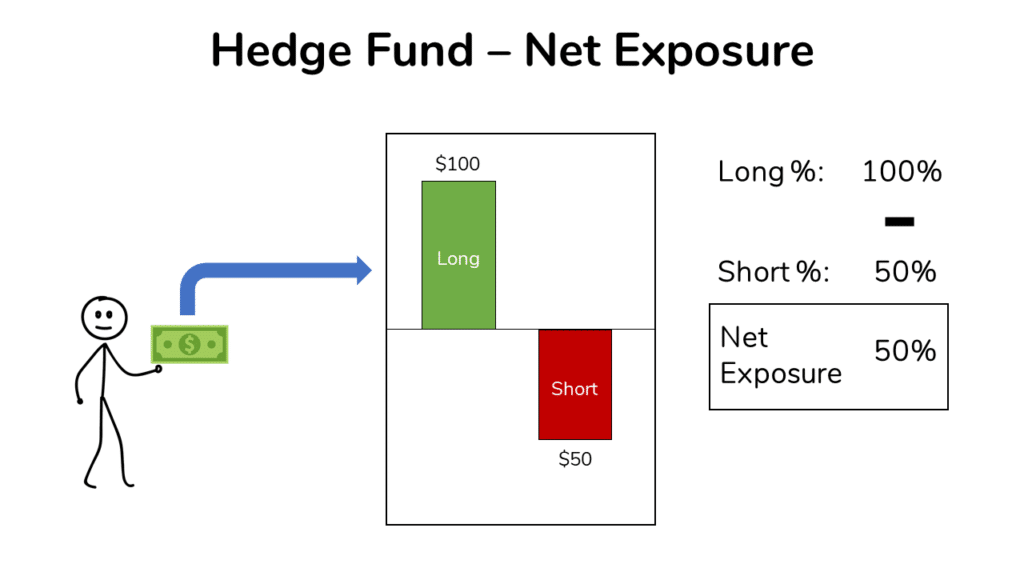

In light of this dynamic, funds also look at a metric called ‘Net Exposure.’

We calculate Net Exposure by looking at the Long Exposure % – Short Exposure %.

In the example above, we have:

- 100% Long Exposure ($100 Long Investments / $100 Investor Capital) and…

- 50% Short Exposure ($50 Long Investments / $100 Investor Capital).

So, we would say that the Fund has 50% Net exposure (100% Long Exposure – 50% Short Exposure).

In industry terms, we would say the Fund is running at a ‘50% Net’ or it’s ‘50% Net Long.’

So, while Hedge Funds do use Leverage, they are typically much less volatile than a similar fund that is 100% Long.

In summary, shorting helps to offset the risk of borrowing.

Hedge Fund Net Exposure – Market Neutral

Let’s take our example one step further and assume that the Hedge Fund manager goes Long $100 twenty Stocks and simultaneously goes Short 20 different Stocks at a total value of $100.

In that case, the Fund’s Gross exposure would be 200%, but the fund net exposure would be zero.

We would call this type of fund ‘Market Neutral.’

This type of Fund should experience very day-to-day low movement (i.e. ‘volatility’) relative to the market.

With that said, it’s also REALLY hard to make money this way because you get basically zero benefit from the movement of the market.

Hedge Fund Risk Factor #3: Derivatives

Another major risk to consider is the use of Derivative Securities.

Before jumping in here, we should note that not all Hedge Funds make extensive use of Derivatives.

So this risk can vary from negligent to significant depending on the Fund.

Just in case you are wondering, we will not be diving down the rabbit hole of the Black Scholes Formula or the intricacies of pricing Credit Default Swaps.

As usual, we will keep it simple.

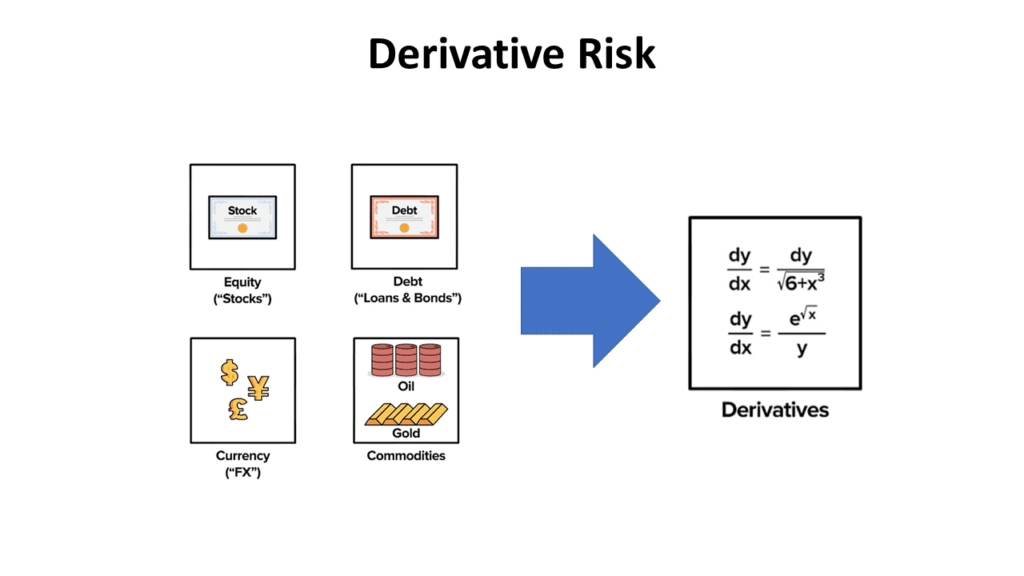

Very briefly, derivatives are instruments that ‘Derive’ their value from another security.

Example of A Derivative: Stock Options

As an example, a Stock Option is Derivative instrument.

Disclaimer: this is a massively simplified example of a Stock Option that disregards time value, volatility, etc.

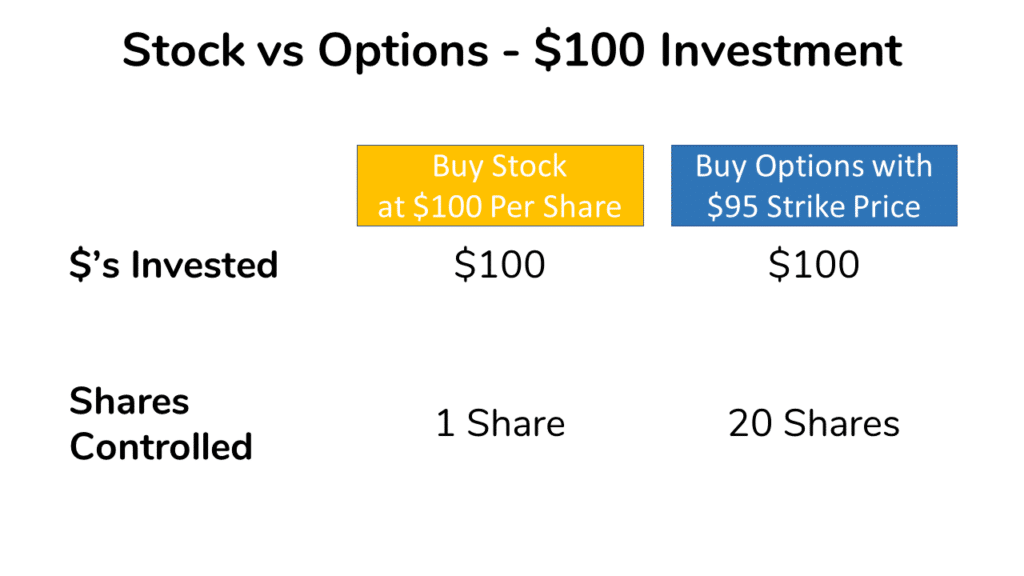

The key thing to understand with Derivatives is that they allow an investor to control large dollar values of a security with a relatively small investment.

For example, let’s say a Stock is trading at $100.00.

And I pay $5.00 for a Call Option that allows me to buy into the Stock above at $95.00 per share.

In this instance, I can control $100.00 of Stock with just a $5.00 investment.

So, if I have $100.00 to invest, I could do one of two things:

- Buy a single share at $100.00.

- Buy options to control 20 shares at $5.00 per option.

In the second example, I would effectively gain or lose from the movements of $2,000 worth of Stock (20 options * $100.00 Per Share).

We would refer to the $2,000 of Stock controlled as ‘Notional’ in the Finance world.

For example, you would hear someone describe the situation above as ‘they bought options with $2K of notional.’

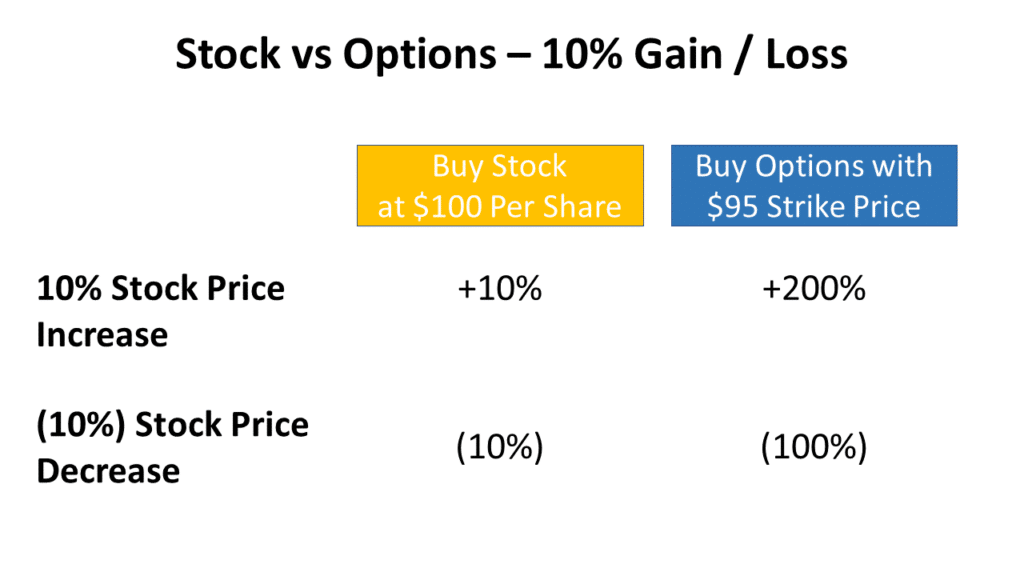

In this example, if the Stock goes up in value to $110, the option would be worth $15 for a cool 3.0x (200% return).

But, if the Stock goes below $95, you lose all of your money.

In short, Derivatives are just another form of Leverage.

Beyond the leverage dynamic, Derivatives are often not as frequently traded as Stocks and Bonds, and pricing them can be incredibly complex (see Black Scholes, etc.).

And so the combination of Leverage and complexity can end in disaster.

The Hedge Fund industry has witnessed a variety of derivative–led blow-ups like Long-Term Capital Management, and more recently, with Archegos Capital Management.

What is a Hedge Fund? – How to Invest

Key Question(s) Covered:

- How can I Invest in a Hedge Fund?

- Who invests in Hedge Funds?

Now let’s dive into how someone can invest in a Hedge Fund.

Before jumping in, I should note that the discussion below is specific to Regulations in the United States.

The rules outside the US vary quite a bit, depending on the jurisdiction.

Finally, the below is in no way meant to constitute legal advice. You should consult a lawyer before attempting to invest in any Hedge Fund.

Legal Requirements to Invest in a Hedge Fund

To begin with, to invest in a Hedge Fund, you will need to meet specific legal requirements.

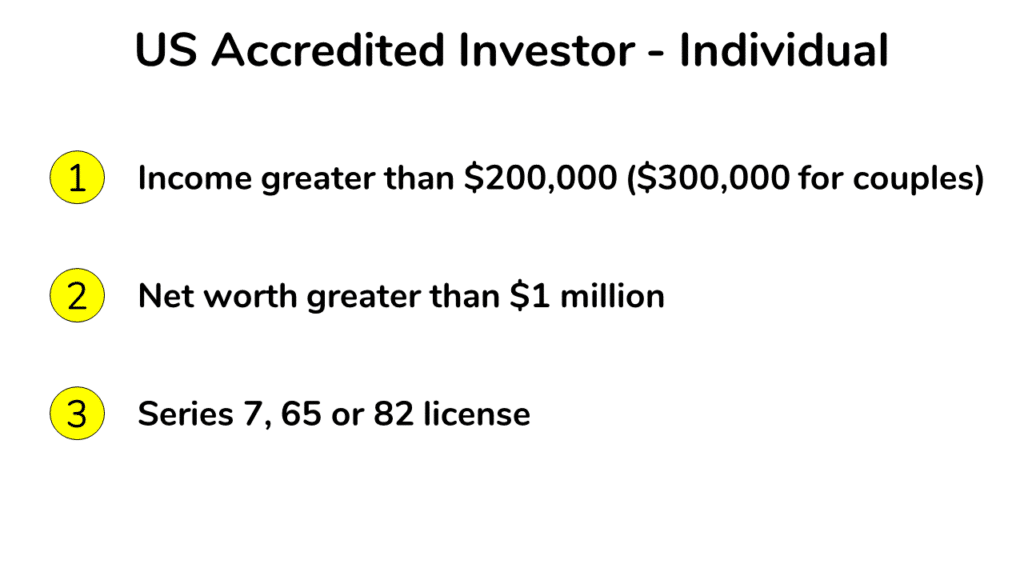

For an Individual in the US, you will need to be an ‘Accredited Investor.’

The criteria to become an Accredited Investor are:

- Earned income that exceeded $200,000 (or $300,000 together with a spouse or spousal equivalent) in each of the prior two years, and reasonably expects the same for the current year, OR

- Has a net worth over $1 million, either alone or together with a spouse or spousal equivalent (excluding the value of the person’s primary residence), OR

- Holds in good standing a Series 7, 65 or 82 license.

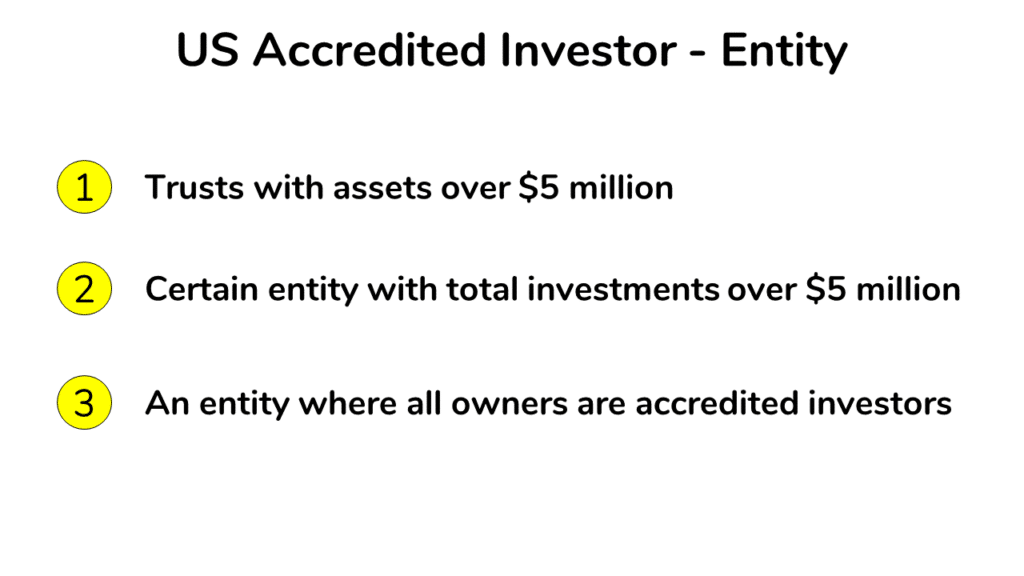

In addition, there are a few other ways to qualify as an entity (as opposed to an individual):

- Any trust, with total assets in excess of $5 million, not formed specifically to purchase the subject securities, whose purchase is directed by a sophisticated person, OR

- Certain entity with total investments in excess of $5 million, not formed to specifically purchase the subject securities, OR

- Any entity in which all of the equity owners are accredited investors.

Source: Investor.gov

Qualified Purchaser Requirements

To invest in some funds, you may need to be a ‘Qualified Purchaser,’ which is an even higher standard:

According to Angelist, “Qualified purchaser status differs from accredited investor status in that it generally depends on the value of a person’s investments, rather than their net worth, income, or credentials. Individuals generally must invest either $5M for themself or $25M for themself and other qualified purchasers to be considered a qualified purchaser.”

As arbitrary as they may seem, the government created these rules to protect individual investors following the Great Depression.

For more on that topic, check out this article.

There have been several initiatives to either change or circumvent these rules in recent years. See these links for more:

- SEC Modernizes Accredited Investor Definition (August 2020)

- What Investors Need to Know About Equity Crowdfunding

Changes to the legal requirements discussed above have opened the door for a broader group of investors to participate in Alternative Investments.

Hedge Fund Investment Minimums

If you can clear the legal hurdles to invest in Hedge Funds, you’ll need quite a bit of money to invest.

Most funds have minimum investments thresholds of $500,000 – $2,000,000 or more.

And the most sought-after funds close to new investors to ensure they can continue to generate attractive returns for their investors.

In short, you will need quite a bit stashed away to get into these funds.

What is a Hedge Fund? – Hedge Fund Managers (+ Compensation)

Key Question(s) Covered:

- What do Hedge Fund Managers do?

- How much are Hedge Fund managers paid?

Now let’s dive into the day-to-day job of a Hedge Fund Manager to see what it looks like behind the curtain.

As a clarification, the roles discussed in this section are specific Long/Short Equity Hedge Funds but most funds roughly operate under similar structures.

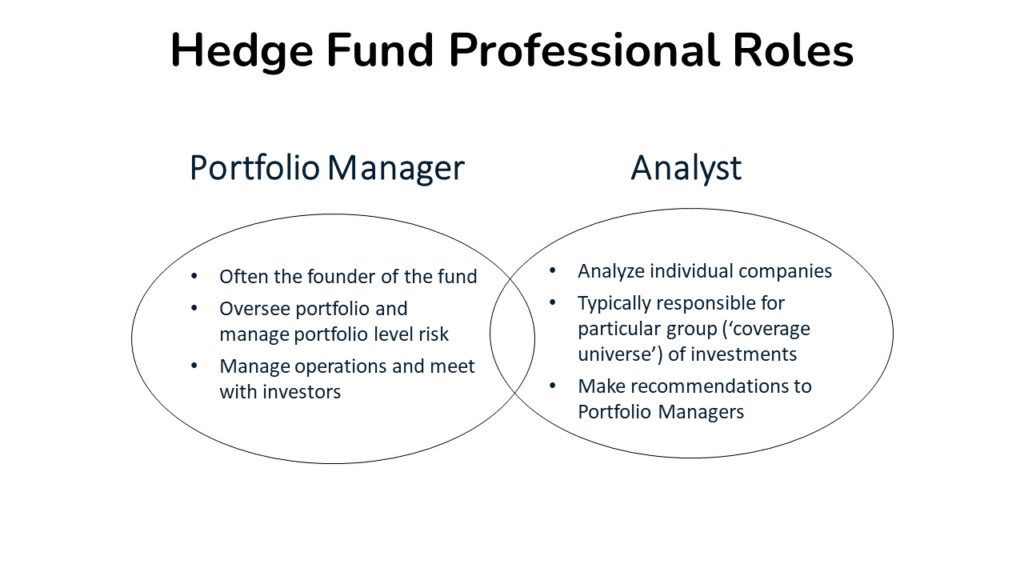

Portfolio Manager vs. Analyst

There are two primary roles in a Long/Short Equity Hedge Fund:

- Portfolio Managers

- Analysts

The Portfolio Manager Role

Portfolio Managers (‘PM’) manage the Fund’s investment portfolio.

In most cases, the PM’s are the Hedge Funds founding Partners.

PM’s look at the bigger picture and ensure that the big picture strategy.

They aim to build a portfolio that can generate outsized returns while simultaneously limiting risk relative to what would be experienced by a 100% Long-Only portfolio.

The Analyst Role

In contrast, an Analyst digs into individual stocks and makes recommendations (i.e., ‘pitches’) to the Portfolio Manager on which Stocks to go Long/Short.

Analysts base their recommendations on extensive company research and company valuations using tools like Discounted Cash Flow analysis.

There are also a variety of other titles at some firms, such as ‘Sector Head,’ which is often a hybrid Portfolio Manager/Analyst role.

To summarize, relative to other areas of the Finance world, there is far less consistency in titles.

Further, Compensation does not necessarily correspond to titles.

There are often instances in which Analysts can make more than their Portfolio Managers.

So while Portfolio Managers are typically at the top of the stack, titles are not very clear-cut in the Hedge Fund world.

Hedge Fund Manager Compensation

The big attraction for many in the Hedge Fund world is Compensation.

If you can generate returns as a Hedge Fund investor, you can build wealth very quickly.

The opposite is also true though.

If you perform poorly as an Analyst, you will likely be asked to leave in pretty short order.

If you perform poorly as a Portfolio Manager, your investors will begin to withdraw their capital.

In total, the Hedge Fund world is high risk and high reward.

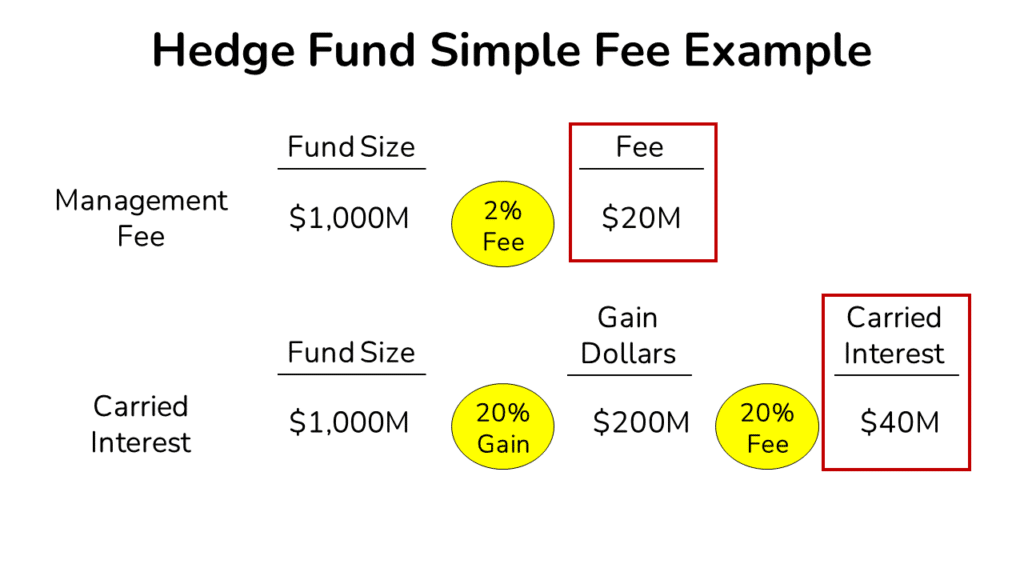

Simple Hedge Fund Compensation Example

Let’s use a simple example to put the potential Compensation for a Hedge Fund Manager into perspective.

We will imagine that a Hedge Fund manager runs a $1 billion fund that generates a 20% return.

And the Fund charges a 2% Management Fee and a 20% Carried Interest Fee.

In a single year, the fund will earn $20 million from the Management Fee and $40 million in Carried Interest ($1 billion * 20% Return = $200 Million Profit * 20% Carried Interest = $40 million).

So, $60 million in total Compensation. Not bad for a year’s work.

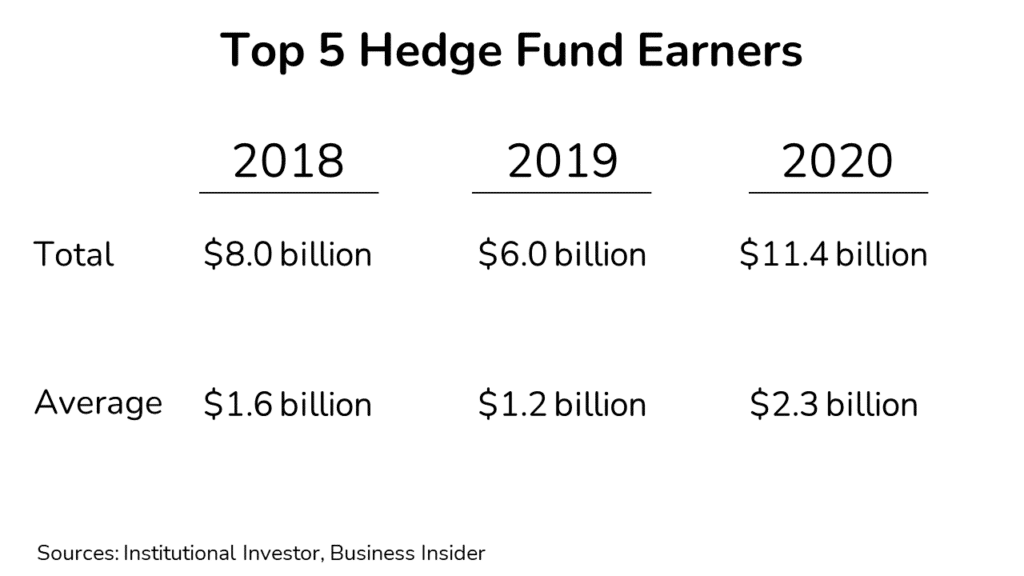

Top Hedge Fund Earners

In the last few years, the top Hedge Fund founders have earned over $1 billion in a single year.

Below are links to the list of the top Hedge Fund earners in recent years:

Now, let’s step down from the stratosphere for a second and look at the ‘typical’ Hedge Fund professional.

Depending on the role, Hedge Fund Analysts will typically make at least $150-200K at the junior levels and Portfolio Managers routinely make over $1 million per year or more, with some making $5 – 10 million or more.

For some additional data points, check out:

- Wall Street Oasis Hedge Fund Compensation Report

- HFM 2020 Compensation Survey

- Institutional Investor Average Pay – 2018

- Sumzero 2017 Compensation Report

With all of the above said, Compensation in the Hedge Fund world varies massively year-to-year depending on the returns generated by the firm.

In short, there is a lot of opportunities, but it’s a long, hard road. Very few make it to the top.

Due to the steep legal and minimum investment hurdles, the vast majority of the dollars invested in Hedge Funds come from large Pensions, University Endowments, and Foundations. (More on that here)

Hedge Funds vs. Private Equity vs. Mutual Funds

Key Question(s) Covered:

- What is the difference between a Hedge Fund and Private Equity?

- What is the difference between a Hedge Fund and a Mutual Fund?

Now let’s look at a brief comparison of Hedge Funds vs. Private Equity Funds and Mutual Funds.

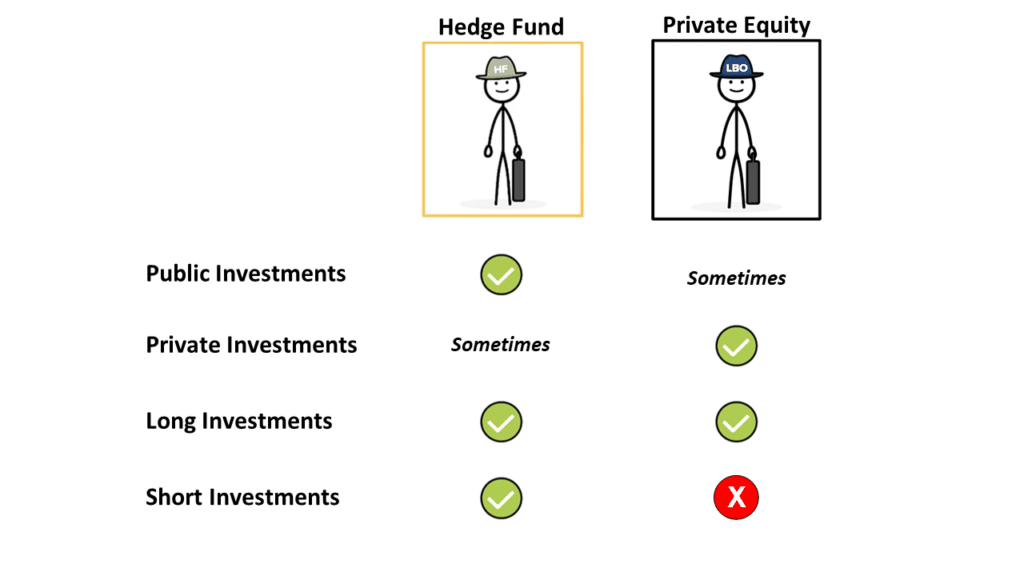

Hedge Funds vs. Private Equity

As the name suggests, Private Equity (or ‘LBO‘) funds typically invest in private, illiquid assets.

PE Investments can range from partial ownership in young, privately-held businesses to full ownership of a company.

In contrast, regardless of strategy, the ‘typical’ Hedge Fund invests in much more liquid securities.

With that said, the lines between the two are often quite blurry.

There are many Hedge Funds that make private investments (and vice versa).

Regardless of the investments made, Private Equity and Hedge Funds are more similar than they are different regarding legal structure and fees.

Both Private Equity funds and Hedge Funds typically utilize the partnership structure.

And most charge fees based on some variant of ‘2 and 20’ fee structure discussed above.

For a deeper dive into the different types of Private Equity funds, check out our highly-ranked Private Equity vs. Venture Capital article.

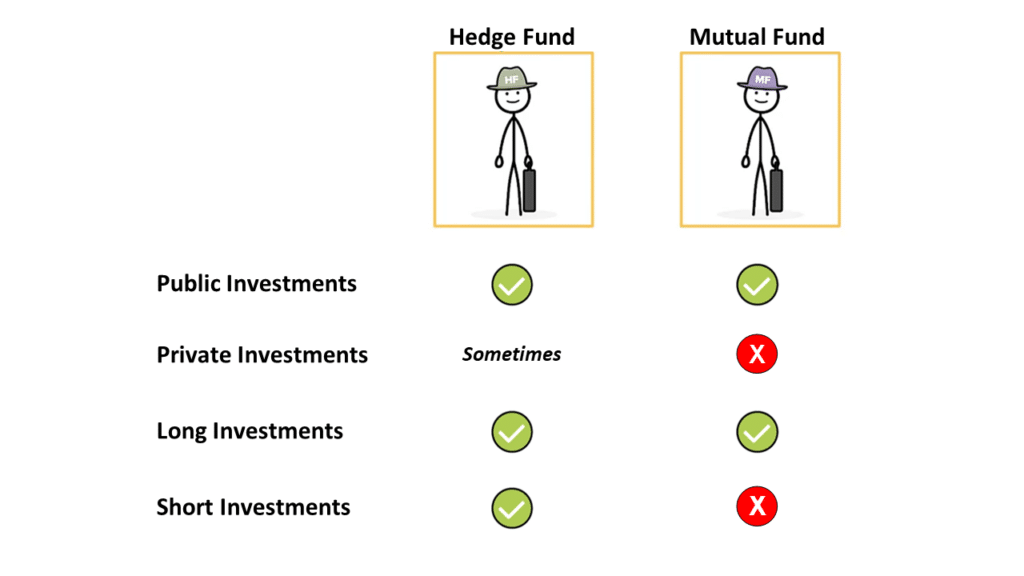

Hedge Funds vs. Mutual Funds

Equity Mutual Funds are very similar to Equity Hedge Funds in that they both invest in stocks.

But that’s where the similarities end.

Below is a brief summary of the key differences between Hedge Funds and Mutual Funds.

For a deeper dive into the differences between these funds, check out our highly-ranked Hedge Funds vs. Mutual Funds article.

Wrap-Up: What is a Hedge Fund?

Hopefully, you now have a much better understanding of how Hedge Funds work.

So the next time someone asks, ‘What is a Hedge Fund?’, you can confidently explain their inner workings.

We hope you found this article helpful and would love to answer your questions (or hear any comments) in the section below. We’d love to hear from you!

About the Author

Mike Kimpel is the Founder and CEO of Finance|able, a next-generation Finance Career Training platform. Mike has worked in Investment Banking, Private Equity, Hedge Fund, and Mutual Fund roles during his career.

He is an Adjunct Professor in Columbia Business School’s Value Investing Program and leads the Finance track at Access Distributed, a non-profit that creates access to top-tier Finance jobs for students at non-target schools from underrepresented backgrounds.

Frequently Asked Questions

A Hedge Fund is a pooled investment vehicle that invests on behalf of a group of investors. The key differentiator for Hedge Funds (vs other types of funds) is that they ‘hedge’ their portfolio by going Short.

To invest in a Hedge Fund in the United States you typically need to be an Accredited Investor or Qualified Purchaser. You will also typically need to invest US$1 million or more to meet the minimum investment requirement of a Hedge Fund.

Hedge Fund managers oversee a portfolio of Long and Short investments and the day-to-day operations of the Hedge Fund.

Hedge Funds typically charge two fees: 1) a 2% annual Management Fee on the money they manage and 2) a 20% cut of the profit (‘Carried Interest’) the fund generates for investors.